Why 'If You Can't Say It, Don't Eat It' Is Bad Advice

By:

The cautionary maxim "If you can't pronounce it, don't eat it" seems, on the surface, like good advice.

After all, our food seems more heavily processed and loaded down with additives than ever before, and it's not clear from scientific research what long-term effect these have on us. Some additives are even banned in other countries, though not in the United States.

Steering clear of hard-to-pronounce names and strange sounding compounds is an easy way to eat healthy and avoid potentially toxic chemicals, right?

Not necessarily.

This bit of common sense wisdom was coined by food writer and activist Michael Pollan, who included it as a tip on "how to eat for a healthier body and planet" in a National Public Radio story from 2008 to promote his book "In Defense of Food: An Eater's Manifesto":

"Don't buy products with more than five ingredients or any ingredients you can't easily pronounce."

What he was specifically referring to were foods reformulated or processed to remove elements deemed unhealthy (think fat in the '90s, carbs in the 2000s, or gluten now) and with extra vitamins and minerals added. So we think the food is good for us — and we unwittingly overeat, adding to the problem.

But Pollan's maxim has fueled an unreasonable fear of chemicals, toxins, and additives. It's been adopted by both mainstream food writers and unreliable food crusaders — such as the "Food Babe," the originator of the groundless hysteria around azodicarbonamide, a safe and useful chemical found in both consumer products such as yoga mats and in bread products.

In its worst interpretation, Pollan's motto is a simplistic appeal to our fear of the unknown. Yes, you can read the label to a packaged food and see it's got ingredients you can't pronounce and additives that do things you don't understand.

Is that bad? What is a chemical, anyway? Why are they bad? Can they ever be good? What makes some substances good and some not good? And what's in a name?

Cornell professor Robert Gravani has been a leader in responsible and reasonable food science and has pushed back at the faulty logic behind Pollan's motto.

In a 2012 interview with National Public Radio's Talk of the Nation, he laid out the valid reasons why food manufacturers add chemicals to food:

"[We] want to enhance the quality and maintain the freshness of foods. We want to reduce waste. We really want to make more foods readily available to consumers. And when feeding 310 million people in the United States, we really need to think about how we can transport this food."

FoodMatters.TV/Pinterest - pinterest.com

FoodMatters.TV/Pinterest - pinterest.com

Gravani pointed out that many hard-to-say additives that push foods past Pollan's five ingredient limit actually do important things:

- Iodized salt seems harmful – but it's the reason goiter has all but disappeared in the U.S.

- Niacin is now added to bread and has all but eliminated the once-epidemic nutritional deficiency pellagra.

- Weird sounding terms like "hydrolyzed" and "autolyzed" and "sulfate" all have scientific meanings that aren't scary at all if you study them even a little.

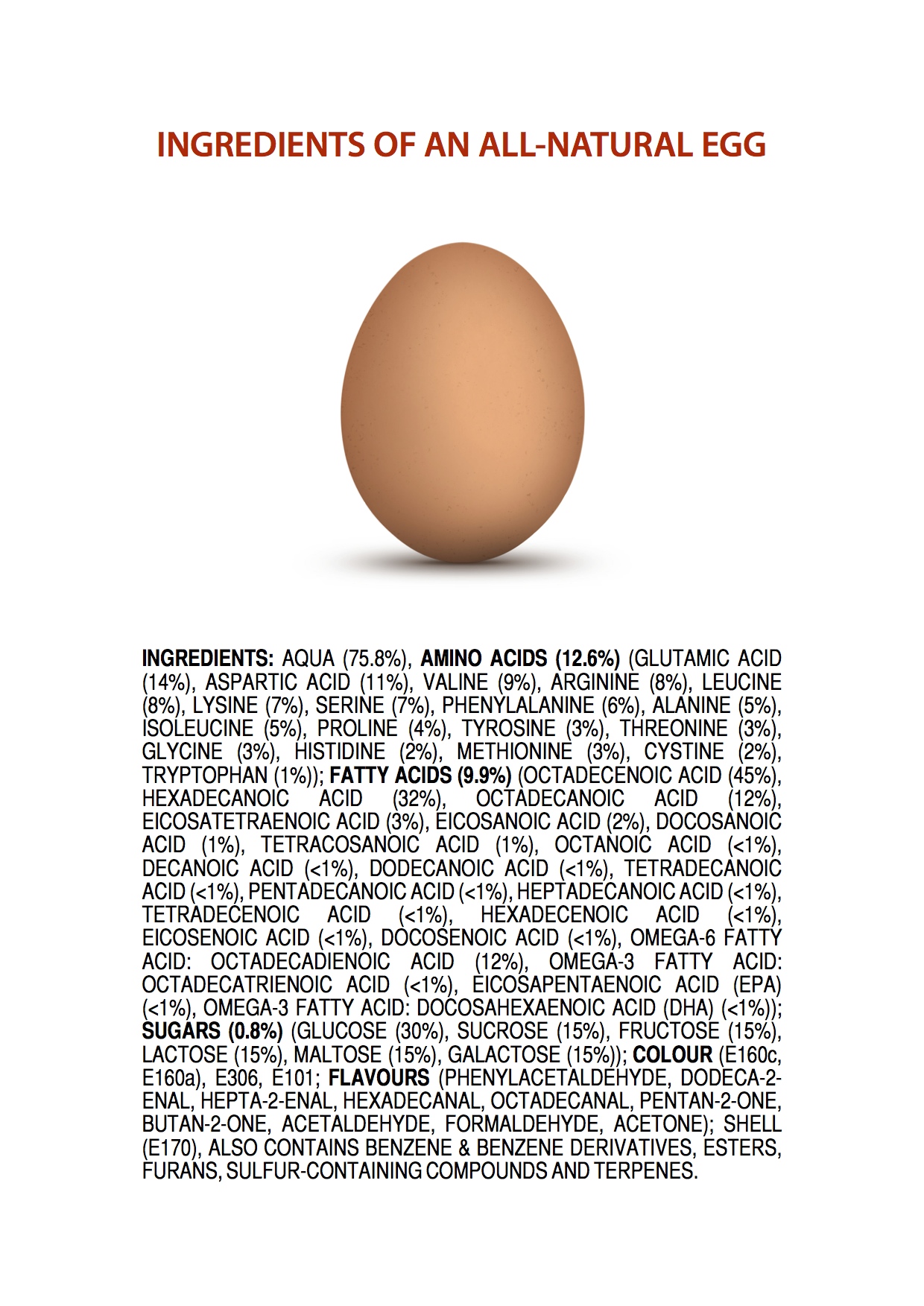

In fact, if you took Pollan's advice to the extreme, you'd starve. "We are chemicals," environmental chemist Dorea Reeser wrote in a blog post for Scientific American. "Our friends are chemicals. Our babies are chemicals. The air we breathe is chemicals. The food we consume is chemicals that are digested by chemicals that turn them into more chemicals."

James Kennedy Monash - wordpress.com

James Kennedy Monash - wordpress.com

Eating food free of chemicals is quite literally impossible, and many common elements that are vital to good health and continued living have some of the hardest-to-pronounce names. Tongue-twisters like menatetrenone, ergocalciferol, and cyanocobalamin are all the chemical names of vitamins. Multi-syllabic monsters like dihomo-γ-linolenic acid, docosatetraenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid all sound like killers but are really unsaturated fatty acids that are essential to good health.

Boiling Pollan's advice down to the molecular level might seem mean-spirited, but it's also useful. Science and chemistry are rarely as cut and dried as "if you can't pronounce it, don't eat it."

Maybe the more helpful motto should be "if you can't pronounce it, research what it does." Or, to put it more bluntly, in the words of popular science blogger and activist Yvette d'Entremont: "If you can't pronounce it, get a dictionary! Go out in the world and learn something."