It's Time We Started Talking About Transit as a Civil Rights Issue

By:

Talk about urban inequality in a city like Los Angeles, and you’re almost certain to hear this oft-cited factoid: some lifelong residents of Compton have never seen the ocean.

If you’re unfamiliar with LA’s geography, that’s a pretty astonishing fact. Manhattan Beach sits a mere 11 miles from Compton. Long Beach is even closer. Even given the infamous traffic on the 105, you should be able to get to the shore in an hour.

Like many well-loved local sayings, it's impossible to fact check. However, the sentiment does communicate a larger truth.

Compton is a poor neighborhood, and owning a car is expensive. In 2015, the Automobile Association of America estimated the annual cost of owning and operating a vehicle at $8,698 — and that doesn’t include the cost of buying a car. That’s just the maintenance, gas, insurance, and taxes — fixed expenses that are well out of reach for American's living below the poverty line, which hovers around $24,300 per year.

Anyone trying to make it from Compton to the beach without a car would have to do it with public transit. Unlike many neighborhoods in LA, Compton actually has a metro station. Compton Station sits on the blue line of the LA metro, and will take you to Long Beach in 40 minutes. But many homes in Compton are upwards of a mile from the station, which means even getting to the train involves hopping aboard one of Los Angeles’s often unreliable busses. It could take hours. For many, it’s just not worth the hassle.

Luke Jones/Flickr - flickr.com

Luke Jones/Flickr - flickr.com

Now imagine that same situation — not being able to quickly and easily get to the beach — but replace ‘beach’ with ‘office.’ Or ‘college.’ Or ‘job interview.’

While it’s commonplace to talk about transit as an environmental issue, or a quality-of-life issue, it’s time we reframed transit as a civil rights issue, too. Access to the beach is one thing — a small curio illustrating urban inequality — but access to job centers, or access to universities? That’s the source of inequality. And for all the obstacles that our most vulnerable citizens face, sometimes the hardest part of finding work is, well, finding it.

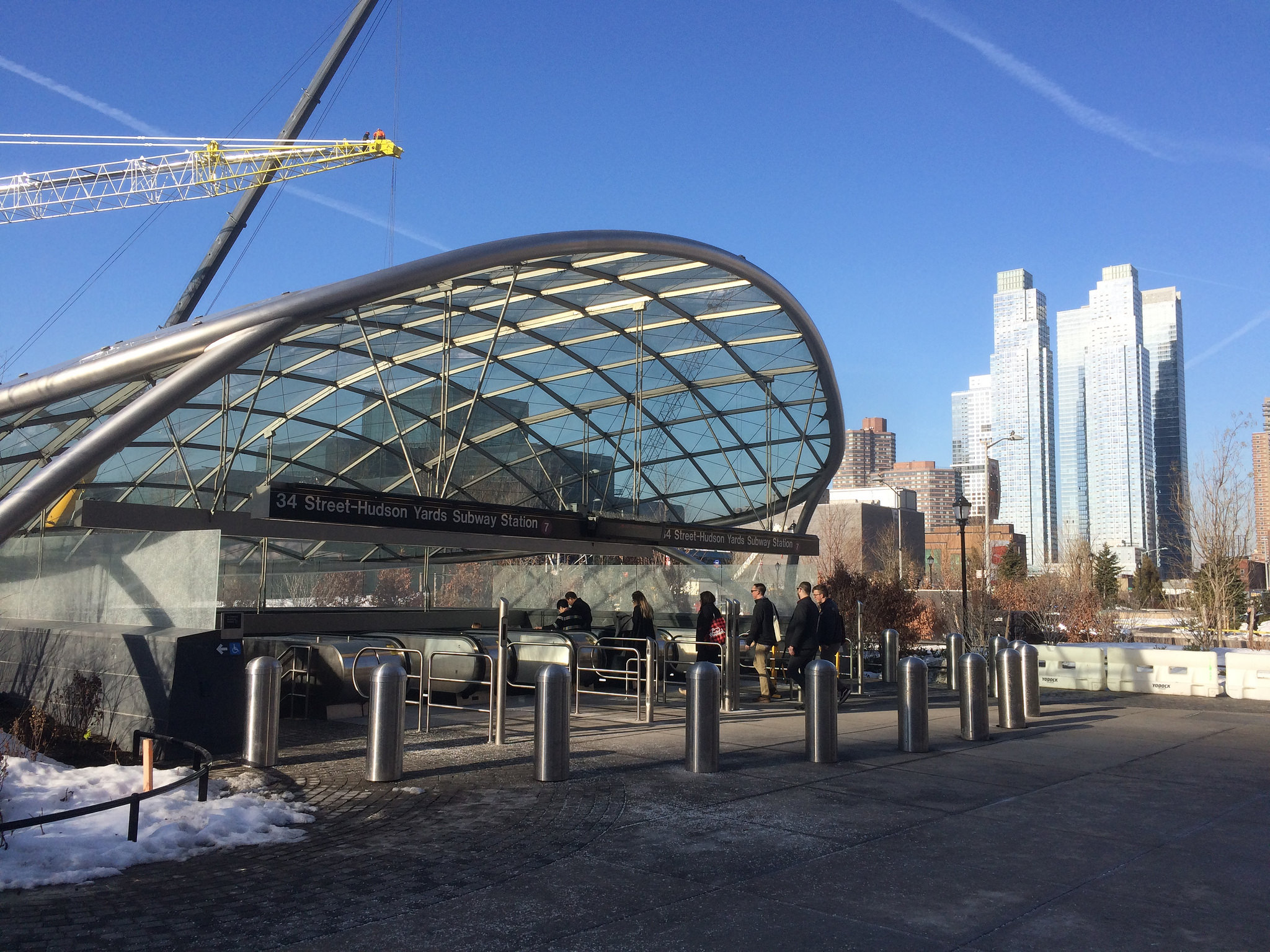

And it’s not just LA. Even in New York City, America’s transit capital, transit expansion has been limited. Those few projects that are in the works are largely going to spur development in wealthy and gentrifying neighborhoods. New York is due to open the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway in late 2016. The revamped Q train will provide additional subway service to the Upper East Side — not exactly a low-income neighborhood. And just a few months ago, New York extended the 7 train to Hudson yards to provide expanded transit service to some new luxury condos. Mayor Bill de Blasio is now promising a tram along the Brooklyn waterfront, providing better transit access to the massive condos of Williamsburg and DUMBO, two once-industrial, now-chic neighborhoods.

Shinya Suzuki/Flickr - flickr.com

Shinya Suzuki/Flickr - flickr.com

Meanwhile those neighborhoods that are well-served by transit are the most ripe for gentrification. Just ask anyone living in Bushwick or Harlem ten years ago. So as transit-dense neighborhoods become wealthier, the people who need transit most are pushed further away from it.

And not everyone sees transit as a priority. In Maryland, Governor Larry Hogan recently nixed the Baltimore Red Line project, which would have created a cross-town subway linking West and East Baltimore to job centers downtown. It would have made it easier for Baltimore’s most vulnerable residents to find work, or get an education.

According to the Baltimore Sun, when Governor Hogan nixed the rail project, he also announced $2 billion in spending on new roads for the rural — and red-leaning—eastern and western reaches of the state. In December of 2015, the NAACP filed a federal complaint against Hogan for scrapping the red line, arguing that the move discriminates against black residents.

The isolation of our inner cities is often discussed in terms of opportunity, in terms of culture, in terms of education. But rarely do we think about our inner cities as being physically isolated. They’re just a mile away. But while there might not be a literal wall around our inner cities, the isolation imposed by a lack of investment in public transportation is very real. As ProPublica journalist Alec MacGillis writes of Baltimore:

"Transportation, or rather the neglect of it by ineffectual local leaders and a state government that had scorned the city from its founding, had helped perpetuate the inequities that remained following the flight, with whole swaths of the city so isolated that they may as well have been under quarantine."

Adam Moss/Flickr - flickr.com

Adam Moss/Flickr - flickr.com

Our transit policies should correct for the isolation of our inner cities, not reinforce it. In the 1960s, we bussed schoolchildren across town to integrate our cities, to give minorities access to greater opportunities, and to build a more just and righteous society. But this begs the question: why haven’t we extended that same idea to all age groups? Why did school busses make expensive trips across town while city bus service got cut? Why was integrating our schools seen as a priority, but integrating our communities deemed unnecessary?

Investment in transit for our most vulnerable citizens not only paves the way for expanded economic opportunities — it’s also a moral imperative. The more we integrate our poor citizens into the fabric of our society, the less the rest of us will be able to ignore them.