How Your Thanksgiving Turkey Gets to Your Table

By:

Unless you're vegetarian, turkey is a staple of the Thanksgiving experience. The National Turkey Federation estimates that 46 million turkeys were consumed in the U.S. last Thanksgiving.

Most people's interactions with Thanksgiving turkey don't go beyond cooking and eating it once every November. But where does our turkey come from, and how does it end up on our table?

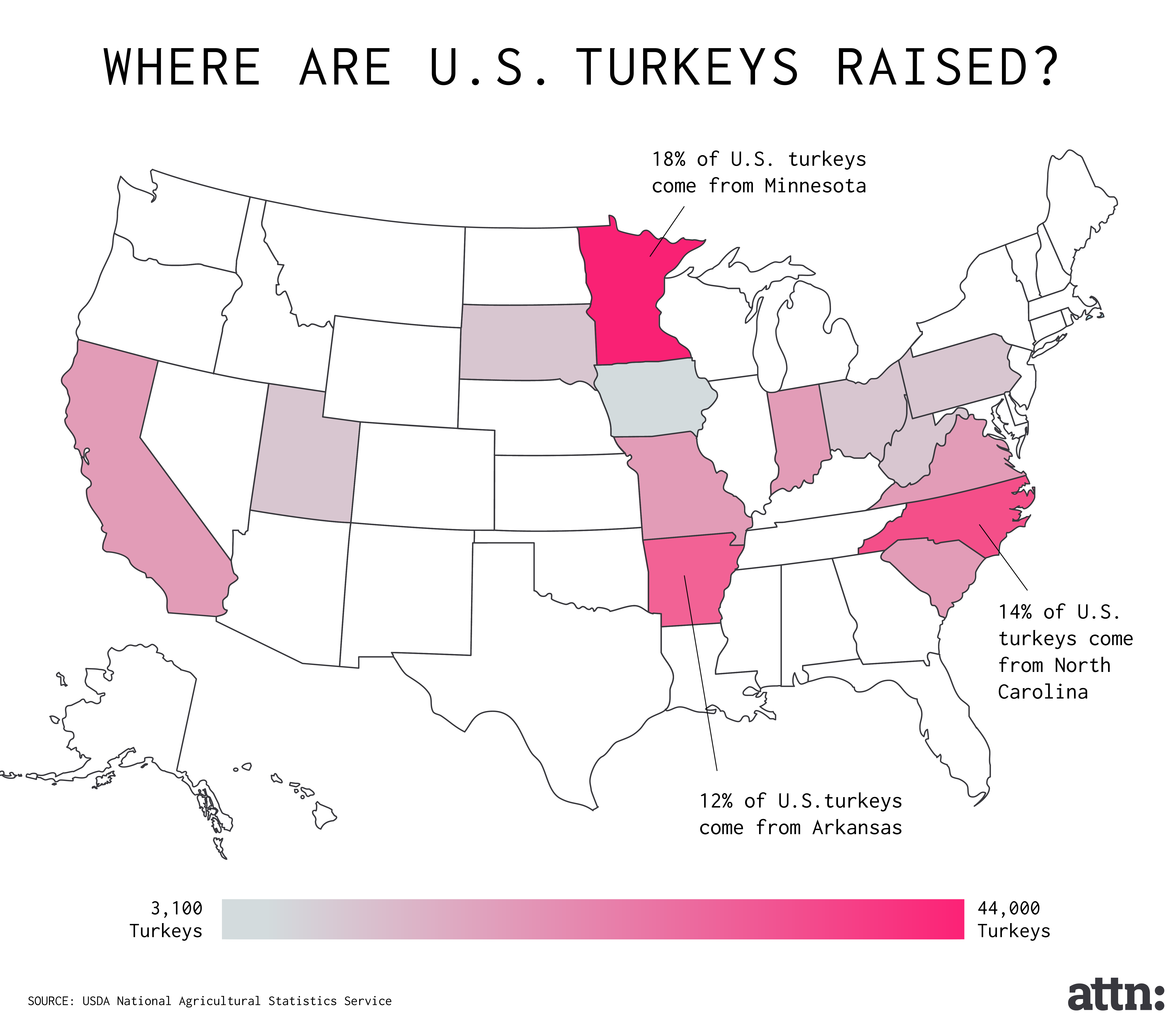

No matter where you live in the U.S., your turkey probably came from the South or Midwest. The top 10 turkey-producing states in 2016 are Minnesota, North Carolina, Arkansas, Indiana, and Missouri, according to the National Turkey Federation.

ATTN/Vocativ data - vocativ.com

ATTN/Vocativ data - vocativ.com

“Most livestock you can produce almost anywhere, but in the U.S., turkey production is concentrated in [the] upper Midwest,” Mark Jekanowski, field corps branch chief of the USDA's Economic Research Service, told Smithsonian Magazine in 2012. “The driving factor for the Midwest is the abundant feed supplies in that region, which is the biggest input cost for farmers.”

Marianne H. Gravely, a senior technical information specialist at the USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), told ATTN: in a phone interview that all turkeys are visually inspected by USDA veterinarians at turkey slaughtering plants to make sure the process meets USDA regulations:

"[The turkeys are] checked over while they're still living for disease. We have inspectors throughout the plant make sure they're slaughtered humanely, that the process is operating properly and in sanitary conditions, according to our regulations. These are big slaughter plants run by big companies, for the most part, so they have certain standards. The USDA inspectors are there to make sure that the whole process is run the way its supposed to be: so that the turkeys are slaughtered humanely and quickly and that the whole procedure goes the way it is so that when the turkeys finish, they're safe. The inspectors do visually inspect the turkeys as they're going by on a conveyor belt and I know it can seem like the conveyor belt is moving pretty quickly, but you have to remember that these are all raised on a healthy diet. It's easy to tell when something stands out. They might be moving fast but they all look the same, so if there's any kind of sign of disease and injury, it's easy for the inspector to pull that turkey off the line. Either it might be re-inspected to figure out what's wrong with it, but that's what their job is. To not only make sure that the process is safe, but that the animals are healthy as they go through slaughter."

As ATTN: noted last Thanksgiving in a piece about the growth in the size of turkeys over time, the turkey breeding process has changed overtime. Breeders started increasing the size of turkeys in the 1950s due to the bird's growing popularity as a dish in our country, as Suzanne McMillan of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals told Mother Jones in 2014. Many of the birds are intentionally bred so large that they can't stand up, Mother Jones reported.

.jpg?auto=format&crop=faces&fit=crop&q=60&w=736&ixlib=js-1.1.0) GETTY IMAGES/KEYSTONE-FRANCE, AP/SUSAN WALSH - gettyimages.com

GETTY IMAGES/KEYSTONE-FRANCE, AP/SUSAN WALSH - gettyimages.com

After an egg is laid — the product of artificial insemination — it gets sent to a hatchery, where it typically hatches in less than a month, Business Insider reported in 2011. Once the eggs have hatched, the fattening process begins so that the turkeys will be big and ready for our consumption after going to the slaughterhouse. The slaughtered turkeys are then placed into bags and distributed across the country. That's where you come in:

It should come as no surprise that the turkey-breeding process does not end (nor start) well for the turkeys themselves, but some brands, such as Perdue Farms, have received attention for implementing more humane practices for animal production. In June, Perdue promised to provide more space for animals and put them to sleep before killing them to improve the process as a whole, The New York Times reported.

"As with the vast majority of poultry in America, our chickens and turkeys (with the exception of those labeled organic) are raised on family farms, cage-free in temperature-controlled, enclosed housing with fresh air ventilation," Perdue states on its website.

Gravely, the food safety specialist from USDA, told ATTN: that all turkey producers have to meet the USDA's standards, and that consumers can observe turkey labels to see whether the bird meets their specific needs and interests:

"We don't really have an A team and a B team where we'd say 'these processors are great and these are OK but could do better,' everyone has to meet our standards. You could look on the labels for things that are important to you. So the turkey says 'USDA Certified Organic,' that would mean that it was fed and raised in a certain way, no antibiotics were given to him. One thing that people should know is that no poultry receives hormones. People will always say, 'Well I want a turkey that was raised without hormones.' All turkeys are raised without hormones, as are chickens, so you don't have to worry about growth hormones. Now some of them are raised with antibiotics, but others aren't and that's something you can look for on the label."

Still confused? You can always trust the label at the grocer, or so Gravely said. "Other things people look for are the free range or free roaming birds. For them to be able to put that on their label, they have to submit their claim to us to prove to us that the birds do have access to the outside."

You can get more information on the turkey production process through the USDA's Ask Karen help feature or by calling the Office of Policy and Program Development number at 1-800-233-3935.