How Congress Could Impeach President Trump

By:

Since the moment Donald Trump was elected president, debate over his possible impeachment has been raging. As early as Inauguration Day, The Washington Post declared "The Campaign to Impeach Donald Trump Has Begun," with news outlets around the world calling Trump's removal everything from an inevitability to an unrealistic fantasy.

But impeachment is a complicated and lengthy process, hindered by unclear language and lack of precedent. For Trump to be impeached, extraordinary changes would have to take place in the makeup of the Republican-controlled House, and he'd have to be convicted by two-thirds of what is currently a Republican-controlled Senate.

The founders of the U.S. government were divided on whether Congress should be able to remove the chief executive — if they should, in the words of Benjamin Franklin, "render themselves obnoxious." It was Franklin himself who advocated most strongly for it, fearing that the only other way to get a president out of office would be by assassination.

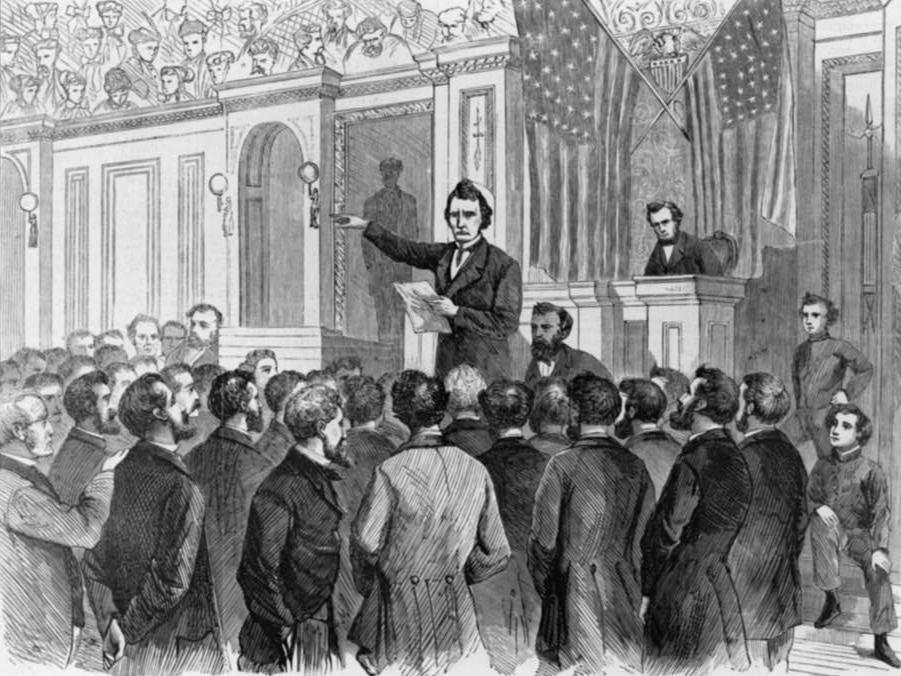

Public Domain - wikimedia.org

Public Domain - wikimedia.org

Using British impeachment law as a model, the founders included impeachment in Article II, Section 4, of the Constitution. The clause allows for the removal of federal office-holders, and specifically the president, pending "impeachment for, and conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

This last term is left undefined, and has caused great consternation in efforts to determine what it actually means.

Public Domain - wikimedia.org

Public Domain - wikimedia.org

Impeaching Trump would require compelling evidence that he'd committed one or more of these acts — and a House willing to investigate him. Removal actually requires five separate votes: two by the House Judiciary Committee, two by the entire House, then another vote in the Senate to convict. The process generally goes like this:

- A member of the House presents charges to the House Judiciary Committee, usually based on a previous investigation.

- The Judiciary Committee votes to request authority from the whole House to begin their own investigation (Vote #1.)

- A majority of the House votes to authorize an investigation. (Vote #2.)

- Once the investigation is complete, the Judiciary Committee votes on individual articles of impeachment. (Vote #3.)

- Once approved, those articles are given to the entire House for a majority vote on each one. (Vote #4.)

- If the House votes to approve any of the articles, the president has been impeached.

- The president is then tried in the Senate, with the House Judiciary Committee acting as "managers," or prosecutors, with the White House counsel defending the president, the chief justice of the Supreme Court acting as the presiding judge, and senators forming the jury.

- Once both sides present testimony, the Senate votes on each article of impeachment, requiring a two-thirds majority to convict (Vote #5.)

- Conviction results in the president being removed from office, but even if the president is not convicted they could still face criminal charges.

Due to its complexity and potential to go wrong, impeachment has been used just 19 times: presidents Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, one senator, one Cabinet secretary and 15 judges have been impeached by the House, with only 8 people ever removed from office. President Richard Nixon had impeachment articles against him approved by the House Judiciary Committee, but he resigned before the full House took up the matter.

All three presidential impeachment proceedings took slightly different paths, making them hard to study as a model for a possible Trump impeachment.

- Loathed by Congress, Johnson had already survived three impeachment votes when the Senate passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867, protecting cabinet officials from being removed. Johnson defied the act to fire his secretary of war; the House voted to impeach just three days later. Johnson's Senate trial dragged on for a month, and he was acquitted by one vote.

- A year-long investigation by Independent Counsel Ken Starr accused Presidnet Clinton of perjury and a range of other "high crimes." The House Judiciary Committee voted in October 1998 to begin an inquiry, with the full House quickly voting to draw up articles. In December, Clinton was impeached on two of four articles, but he was easily acquitted in the Senate.

- In October 1973, following Nixon's firing of the Watergate Special Prosecutor, Judiciary voted to begin an inquiry. In February 1974, the House voted to authorize drafting articles of impeachment. It was during that investigation that Nixon's White House taping system became public knowledge (he recorded almost everything). Judiciary voted to authorize three impeachment articles in July, and weeks later, Nixon was compelled to release his full, unedited tapes. The tapes destroyed any defense he might have had, and he resigned on Aug. 7, 1974.

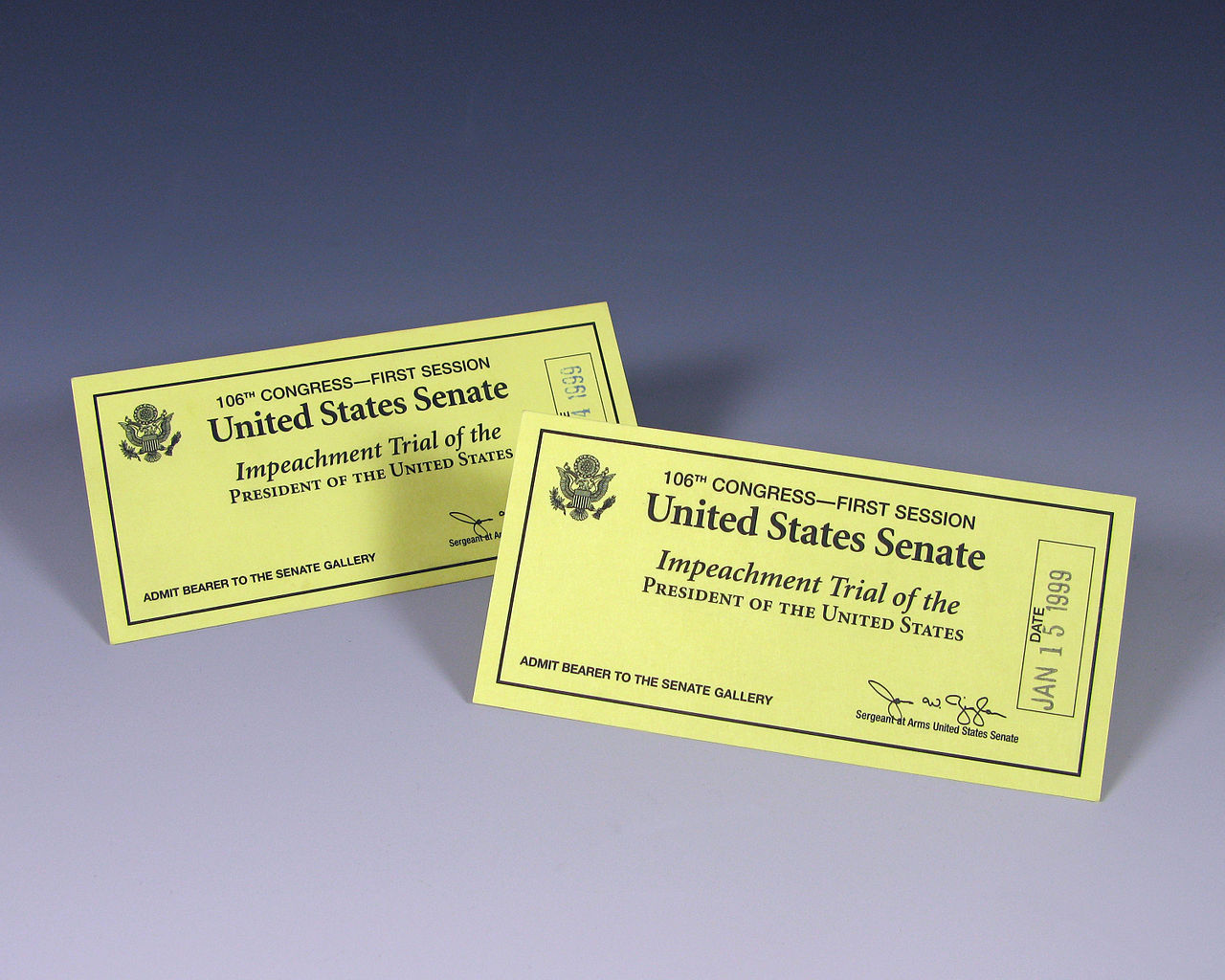

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum - wikimedia.org

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum - wikimedia.org

Impeachment is fraught with peril. It can make Congress look petty and venal, and make the accused a martyr. Clinton's approval rating skyrocketed after his impeachment, for example.

As much as President Barack Obama was loathed by Republicans, he never had even a preliminary impeachment vote taken against him. And while the House did vote to refer impeachment of George W. Bush to the House Judiciary Committee in June 2008; it died without a vote being taken.

A Trump impeachment would require a Republican (at least for now) House to vote twice against a president in their own party — assuming a Republican House Judiciary Committee would let it get that far. Even then, Democrats would still need nearly 20 Republican senators to cross party lines to convict in a trial. The process would likely drag on for years, and have no conclusive ending.

But if Democrats can re-take the House in the 2018 mid-term, or Trump becomes so unpopular that his own party turns on him, impeachment becomes much more likely. Or at least, much easier.