Bosses Steal a Staggering Amount From Their Employees

By:

When an employee is caught stealing from a boss, the consequences are often swift, and with at-will employment, not subject to appeal: You’re fired and if the cops are called you might also end up jailed. When a boss steals from an employee, however, it’s a bit more complicated.

U.S. employers steal a lot, though, and the lack of serious consequences plays a part. When researchers surveyed over 4,300 low-wage workers in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City, they found that most were victims of some form of wage theft — ranging from unpaid overtime to sub-legal wages. The average victim’s loss was over $2,600 out of the $17,600 in salary they were supposed to be paid; that comes out to more than $50 billion in wage theft every year, nationally.

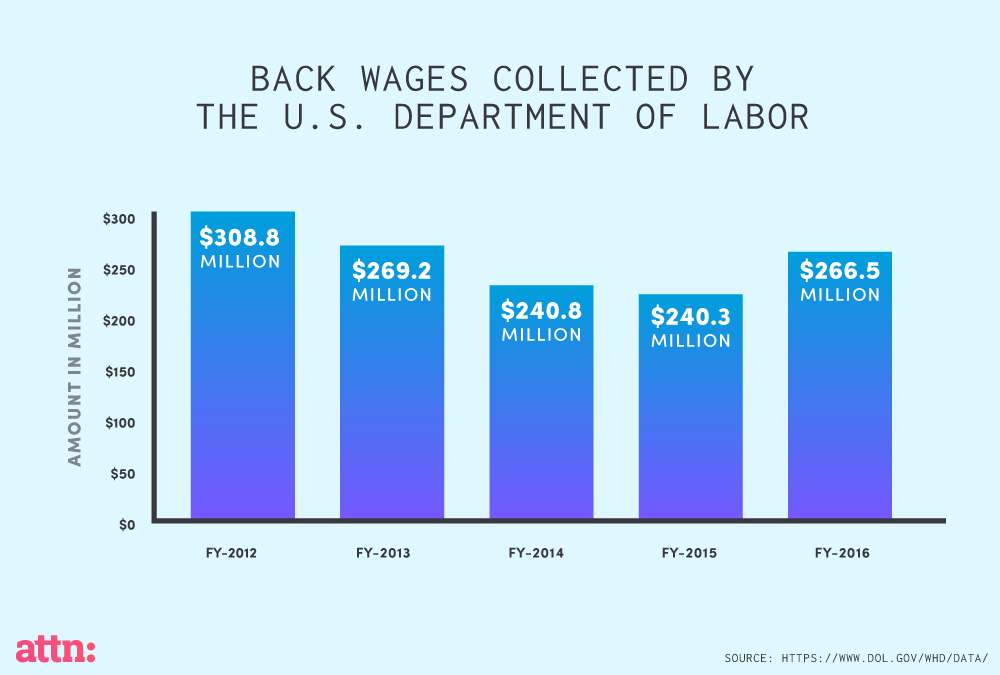

Recovering these stolen wages is the job of the roughly 1,000 investigators with the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division; they helped over 283,000 employees recover more than $266 million in 2016. But the $1.2 billion in back wages the division has recovered since 2012 is only a fraction of the total theft. There's more employer crime than the division can handle; it now taking over four months to resolve a complaint filed through its website, the wait time has increased 33 percent since 2005.

Recovering stolen wages isn't going to get any easier — or faster — under President Donald Trump. In March,Trump reversed an Obama executive order that sought to bar federal contracts from being awarded to companies repeatedly caught stealing from their employees. And now his administration is proposing a 21 percent across-the-board cut to the Department of Labor’s budget.

The implications for the Wage and Hour Division aren't good. This administration is more keen on reducing oversight of the private sector than boosting the power and number of government regulators.

ATTN: sought to find out how the division aims to cope with an expected slashing of its budget, but no one was made available.

“At this time, the Department of Labor isn’t able to provide a subject matter expert for interview,” department spokesperson Edwin Nieves said:.

Peter Walsh/Flickr - flickr.com

Peter Walsh/Flickr - flickr.com

The Department of Labor isn't the only help available for victims of wage theft: community groups are picking up the burden at the local level.

Marianela Acuña Arreaza is the executive director of the Fe y Justicia Worker Center in Houston, Texas. “We get about six calls per day from people who need some help, not just with wage theft but labor abuse cases,” she told ATTN:.

The center picks up the slack left by an under-resourced Wage and Hour Division and the Texas Workforce Commission, helping workers figure out if they have been wronged, legally, and what they need to do to get what’s theirs. Sometimes all it takes to get money workers are owed is a stern letter demonstrating that the victim knows their rights. Other times it takes a lawsuit. The avenues for justice provided by federal and state governments are often the best bet — the employee doesn’t need a lawyer, but they do need time as a wage dispute can take the better part of a year to resolve.

Arreaza dreads the prospect of federal budget cuts.

“I can’t even imagine having less people helping workers out,” she told ATTN:. “It’ll be rough.”

Cutting back on efforts to combat employer theft, in conjunction with stepped up efforts to deport immigrants, signals to unscrupulous employers that they can get away with exploiting the poor and undocumented. And in Arreaza’s experience, that affects anyone who “looks” or “sounds” like that may be the case. "I think a lot of the times it's related to racial profiling," she said.

Gilberto Estrada is a U.S. permanent resident, originally from Ecuador, who got hurt in an accident while moving cargo in an 18-wheeler. After the accident, he told ATTN:, his employer went AWOL, perhaps assuming that because Estrada’s English was limited he would be wary of exercising his right to what he was legally entitled.

“They owed me my final check,” he said. “I tried to call both my manager in Houston and his manager in the headquarters in Chicago. And they were kind of like avoiding me, and then they stopped answering my calls.”

The Fe y Justicia Worker Center helped him draft a letter that showed he would fight for what he was owed, legally if need be. It worked.

“That’s what made them react,” he said. Estrada ended up getting just over $3,000 in back pay and all it cost him was some free time.

It wasn’t so easy for Olga, an undocumented woman from Mexico who has lived in the U.S. for over 20 years. “I was working at a restaurant,” she told ATTN:, “and what happened is my employer stopped paying me because he said his account was frozen by the IRS.” It was a job and she assumed her boss was good for the money, so she continued to work.

When Olga did ask for her money she got checks that bounced. That’s when she threatened to sue. That didn’t work.

“They said they didn’t owe me anything,” she said. “They were saying it would be better for me to be on their good side because they knew I was undocumented. They said I had more to lose than they did.” They offered to give her $500 to go away. They owed her $3,000.

So she followed up on her threat and took her boss to small claims court, where she won. Now she assists others like her at the center. “It’s a place where I can help people searching for their rights,” she said. And particularly in Texas, and with cutbacks being eyed in Washington, “they need volunteers to help other people.”

Eino Sierpe/Flickr - flickr.com

Eino Sierpe/Flickr - flickr.com

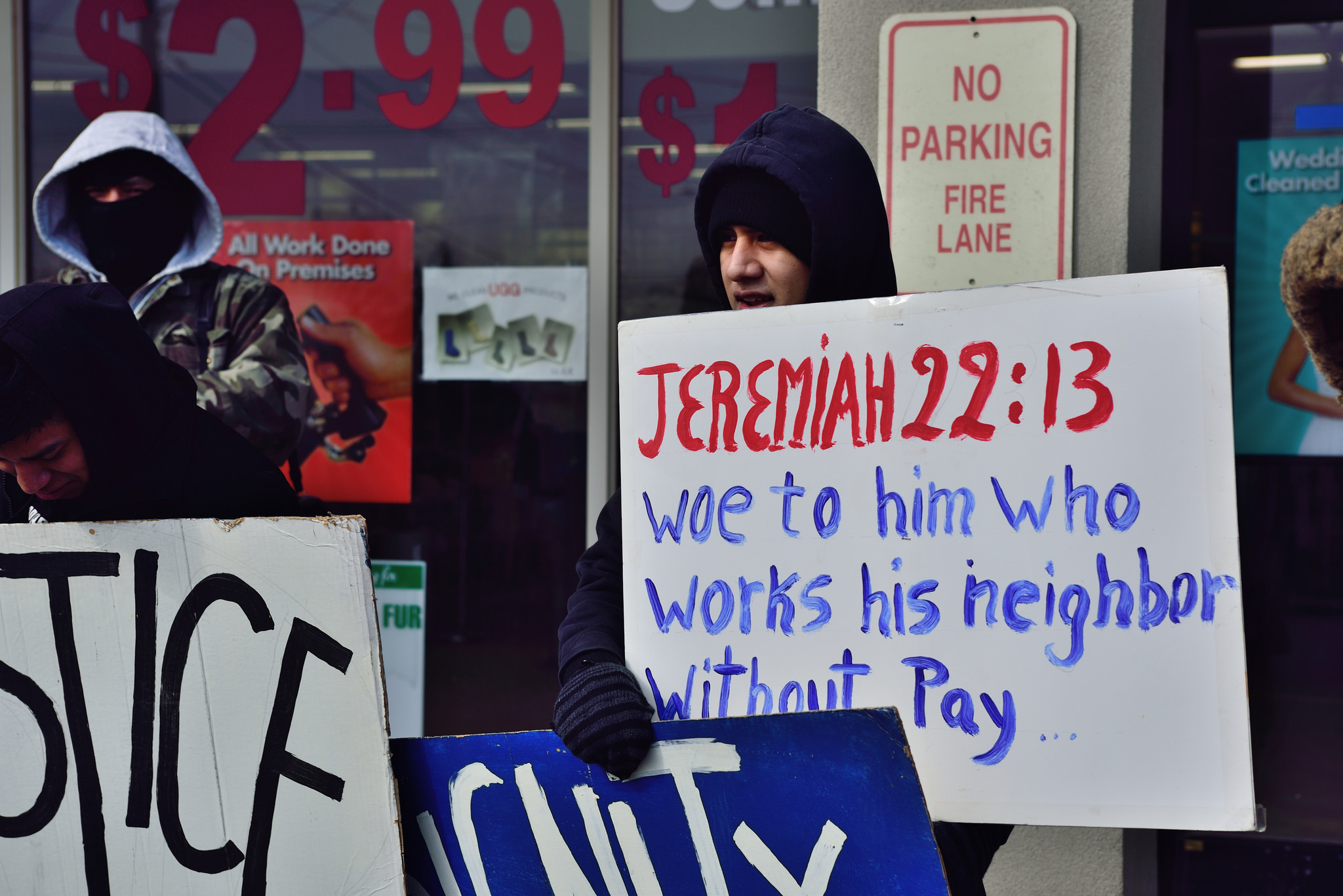

Ian Pajer-Rogers, communications director for Interfaith Worker Justice, told ATTN: wage theft is pervasive. “I think it would be pretty mind-blowing to people,” he said. “It’s really insidious.”

Stealing checks is one of the more obvious forms of theft. But misclassifying employees as "independent contractors" not entitled to benefits or unemployment insurance is another, Pajer-Rogers said, “and we’re seeing that a lot right now with the gig economy” — with companies like Uber and Lyft and other apps that provide incomes but not health care. Others classify entry-level employees as “interns” so as to justify sub-legal wages, while some for-profit companies like SXSW accept "volunteers" that do the work of what, legally, ought to be a paid employee.

Other popular forms of employer crime include not paying overtime; not providing breaks; not meeting the minimum wage; and even compelling employees to work for free if they want to keep their job.

Fighting wage theft can take the form of private letters or public shaming: tweeting or picketing or speaking to the press.

In states like California or Texas, one can also file administrative complaints with the state's department of labor — free but for the time it costs, and the many months it takes to get a decision. The same option is available at the federal level, though there are far more complaints than there are investigators. There is also the courtroom.

There is that discrepancy, though: If an employer is caught red-handed, willfully and without remorse, stealing their employees’ wages, they won't be headed to jail like an employee caught stealing from their employer. It’s an idea some lawmakers have proposed — treating workers and bosses as equals before the law — but efforts to make it so have always stalled.