How Personality Tests Get It Wrong

By:

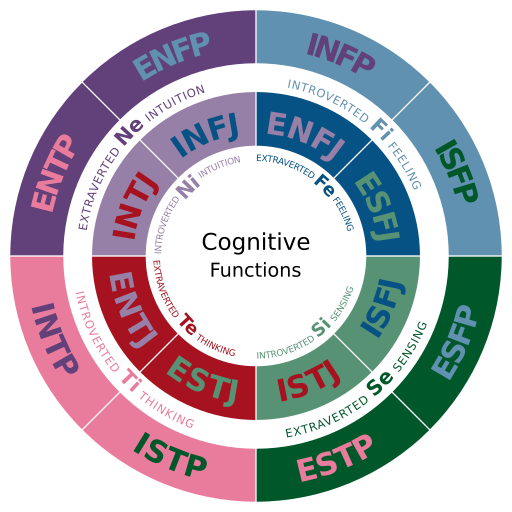

Every year, over 2 million people take the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), which assigns each test taker a 4-letter personality type based on a combination of four binary choices: extraversion/introversion, intuition/sensing, thinking/feeling, and perceiving/judging.

For many of those people, MBTI is more than a personality test: it's a way of understanding themselves. And the influence of the test has even spread to the workplace, with 80% of Fortune 100 companies claiming to rely upon the test for hiring and team building. But while such tests are wildly popular, they aren't exactly clinical.

These tests are not particularly concerned with science.

Most personality tests are novelties. Even the gold standard MBTI—created by a housewife and her daughter in 1943—is largely ignored by the field of psychology.

“Personality testing is an industry the way astrology or dream analysis is an industry: slippery, often underground, hard to monitor or measure,” Annie Murphy Paul, author of The Cult of Personality, wrote for NPR. “Human beings are far too complex, too mysterious and too interesting to be defined by the banal categories of personality tests.”

And in addition to dismissing human nuance, personality tests don’t take into account scientific studies about human behavior. As industrial psychologist Tom Skiba told ATTN:, “In the last 50 years, there has been a bevy of research in personality psychology, behavioral genetics, and neuroscience that have enabled psychologists to create accurate, insightful, and useful tools to assess personality." He added, “The problem is that Myers-Briggs and other tools do not leverage this research."

WikiMedia - wikimedia.org

WikiMedia - wikimedia.org

The problem with putting too much stock in personality tests.

Relying on these non-scientific tests can be problematic, particularly in the workplace. “Making personnel decisions solely based on labeling a person’s ‘psychological type’ is unfair," Skiba said. “Personality tests can be very blunt instruments, more like a cleaver than a paring knife. The shorter the test, the blunter the results have to be, placing people into broad either/or categories. Where is the nuance?"

As Ilina E. Strauss told The Atlantic, “Stereotyping people using the test seems risky at best and harmful at worst. In particular, screening potential employees through the MBTI is probably a mistake, since there’s no proof that you can link MBTI to how effective people will be at their jobs.”

In addition to limiting employee success and creating unfair measures in the hiring process, putting too much weight on personality tests can also cause interpersonal issues. Psychologist Joel Minden told ATTN: that relying too much on personality test results can negatively impact relationships when a person rigidly refuses to adapt to situations because "that's just their personality."

"For example, someone with a high score of introversion might put up a fight if a relationship partner wants to go to a party, and someone with a high score on a measure of conscientiousness might plan excessively and resist a partner's efforts to be spontaneous," he said.

So while they're not inherently harmful, issues arise when personality test results are seen as a sort of destiny.

"Can a right-handed boxer learn how to be a southpaw? Can an introvert deliver a political speech?" Skiba asked, and added, "One of the biggest mistakes people make is assuming that broad personality traits mean that someone is incapable of learning something outside of their comfort zone."