What It's Like to Be Adopted by White Parents

By:

NBC's Emmy-nominated "This is Us," and the Oscar-nominated film "Lion" have put a pop culture spotlight on interracial adoption. As the United States is becomes more diverse, interracial adoption, also known as transracial adoption, has become an increasingly important topic.

Despite its increased visibility, interracial adoption and the race-based challenges that can arise are still a hotly debated topic. Beyond the Hollywood representations, ATTN: wanted to know what it's truly like to be adopted by parents of a different race. ATTN: spoke to five people of color, who were adopted by white parents. Now-adults, their varied coming-of-age stories are filled with obstacles, insights about race and the changing American family, and a lot of love.

What did you parents teach you about race?

The adoptees ATTN: spoke to all described adoptive parents who love them very much, and remain very supportive. One is an only child, one has a sibling that is his parents' biological child, two have adopted siblings and siblings that are their parents biological children, and one has siblings who are all adopted children.

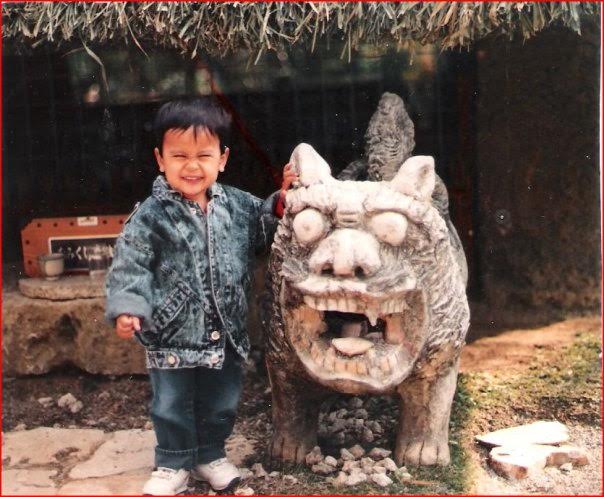

Twenty-nine-year-old Carlos Williams, who grew up in New England, said that his parents always encouraged him to learn about his Filipino culture.

"I remember I was at a party with my parents when I was really young, and there was an old Filipina there, like grandma old, and my parents pretty much forced me to sit on her lap and have her talk to me about the Philippines," said Williams, who now lives in Korea.

Carlos Williams

Carlos Williams

However, he said that in terms of growing up as an Asian person in the U.S., he often had to figure out race issues on his own.

"I had mostly white friends, and so whenever race became a major factor in interactions with people and my environment, I'd sort of be alone in figuring it out," he said. "I think that's a major downside to interracial-international adoptions: we're plucked from one community and thrust into another where there aren't a lot of us around, and we don't really have a net community to become educated in."

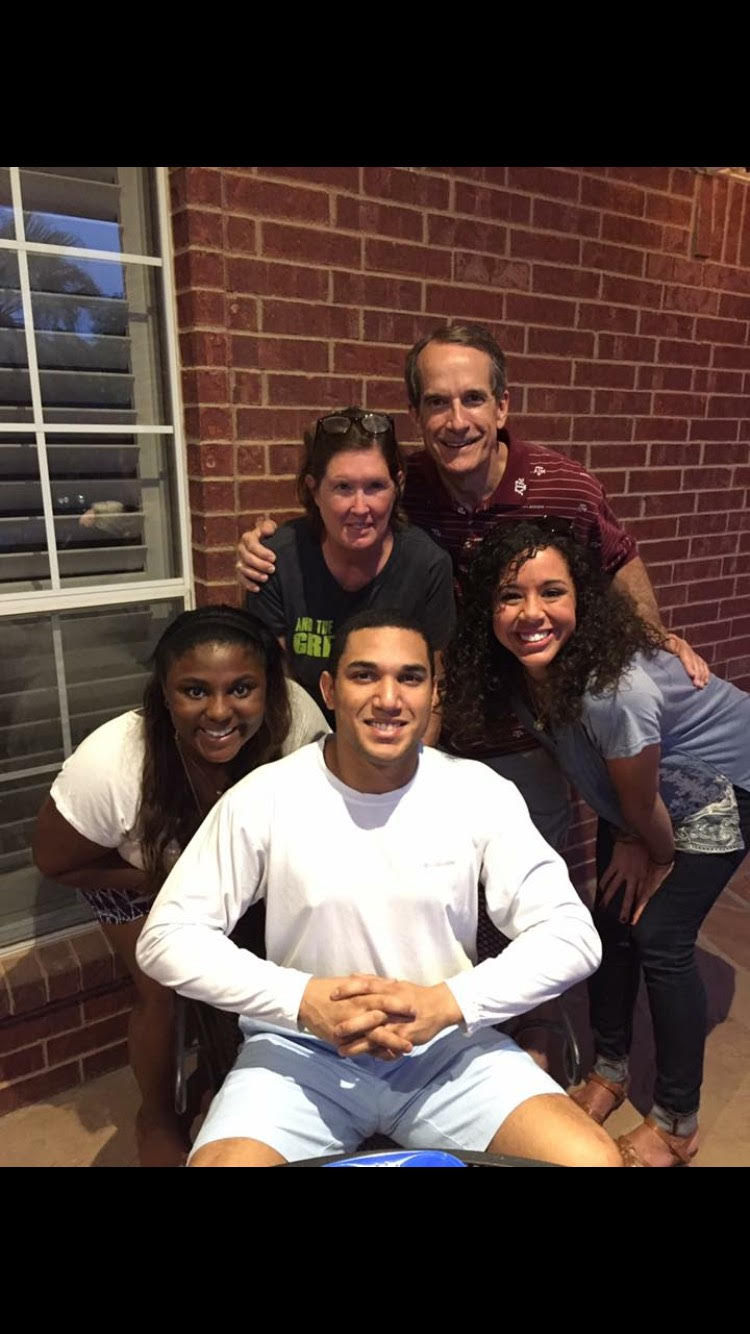

Maddie Whigham, 17, is from Midland, Texas. She said that her parents told her some people would dislike her for being black, but that "they don't know your story, so you just have to shake it off and not dwell on what they said." Whigham said that lesson was important.

"I struggled with that for a while, then I realized I have so many family and friends who love me for the way I am," she said.

Maddie Whigham

Maddie Whigham

Theresa Helmer, a 27-year-old black woman, said that her parents tried to connect her to black culture growing up in northeast Tennessee.

"They have really evolved with the times," said Helmer, who currently lives in Los Angeles. "They're not sitting here giving respectability politics stuff, and they're into Black Lives Matter and intersectional feminism. They see that adoption doesn't really preclude you from having the full black experience so to speak."

One area where racial and cultural differences became obvious for Whigham and Helmer was in the arena of hair. Their hair is a very different texture from their parents' hair and needs different products and styles.

Helmer's mother hired a woman to teach her how to do black hair.

"She was like, 'I want to make sure my kid's situation is right,'" said Helmer. "That's a bare minimum thing, but in the '90s that was a more uncommon thing to do. Now you have YouTube."

Whigham said that women would come up to her and her mother in public and criticize her hair.

"Black women would always come up to me and my mom everywhere we went, some of them were really nice and wanted to help," she said. "But there were a few who weren't helpful at all, and they would come question my mom and ask why did she do this or that."

Maddie Whigham

Maddie Whigham

What was school like for you?

Michael Sullivan is 37 years old and currently lives in Los Angeles. He grew up as an only child—and possibly the only black person in the small community of Freetown, Indiana. He said that when he lived in Freetown, there were only about 350 people in the town.

His biological mother was white and his biological father was black, which was a large part of the reason he was given up for adoption. "Miscegenation was deeply frowned upon in southern Indiana in the late 1970s," he said. "I was actually born in Seymour, Indiana, which has its own troubled history with race."

He said his grandmother in his adoptive family used the word "colored" well into the 1990s, and there were multiple times where school children called him a nigger. He said his mother "fought like hell" to get the school to do something about it, and his dad fought to make sure racism didn't stop him from participating in sports with the other kids. They also found the money to send him to a psychologist when he received death threats in his locker in middle school.

Because he was the only black person he knew of in the community, he felt like he had to be a model minority at all times.

"There were a lot of people that I'd talk to on a day-to-day basis for whom I was the only representation of African-American culture they would ever know," he said.

He would try to be articulate at all times, and he would hide when he studied, so he would seem naturally intelligent.

"First, I really, really pressed hard to seem intelligent. Like, I would speak perfect Standard American English at all times, emulating newscasters as best I could to avoid any hint of a 'black' accent," he said. "And it wasn't enough to just be smart, I had to seem like I was naturally smart."

Sullivan was excited to go to college at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, but he had a hard time relating to the other black students he met.

"I really looked forward to college, but then I didn't really fit in with the black students I met freshman year, and I can't really blame them," he said. "I had literally never had a black friend when I arrived at Ball State, and I was clearly a poser in that culture."

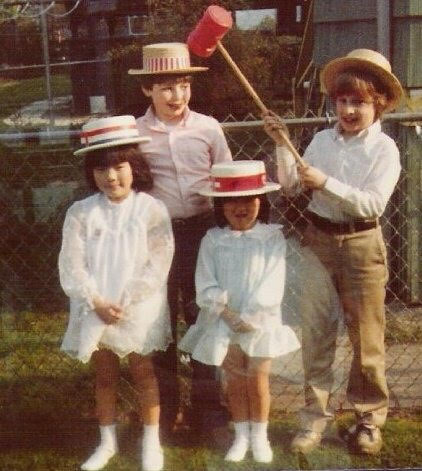

Elin Riggs, 43, is Korean-American and lives in Syracuse, New York. She grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts, was raised solely by her Portuguese-American mom, and attended a mostly white Catholic school.

Elin Riggs

Elin Riggs

However, Riggs said there were only a few times where race was an issue.

"It wasn't until I got to high school that I really noticed a difference," she said. "Someone called me a chink and I really didn't know what it meant."

She said when she got to college at Bridgewater State University, she had a negative reaction to being put in a minority progress program. She called the director and said she didn't want to be in the program.

"The way that it was explained to us was that it was a program for extra tutoring and I didn't think I needed that," she said. "It's interesting that I was fighting it when all they wanted to do was help me."

How has being adopted into an interracial family affected your identity as an adult?

Riggs said that she experiences moments of feeling "in between," but overall she's very comfortable with her identity.

"You kind of feel like you're on the outskirts of both groups," she said. "You kind of feel like you don't fit in with the Asians, because you don't know the food and culture, but you don't fit in with the white kids because you're not white."

Riggs was not raised with any connection to Korean culture, and she is ok with that. However, she said it could be more important for children of other races.

"I have some close friends who are black, and there is a white gay male couple raising black daughters, and they have disregarded their heritage completely," she said. "My black female friends are very troubled by that."

She said she is comfortable identifying as an Asian woman, but she has no interest in going to Korea to look for her birth family, partly because it could hurt her mother.

"If you're an adoptee it's a very emotional thing to go through, and I don't need to do that," she said. "I wouldn't search for my birth family, because I know my mom wouldn't really be ok with it. Why would I do something I know would hurt her when it's not really important to me?"

Williams, however, found it important—and even transformative—to visit the Philippines after college, saying it changed the way he felt about himself for the better.

"I didn't go over there expecting some grand spiritual homecoming, or for all these answers to come flooding over me," he said. "I just had to get over there to see everything. I got to see the village I was born in and all the people who could have potentially been my neighbors or cousins."

He said that when he came back he felt more in touch with his Filipino heritage and more at ease with the various parts of his identity.

"When I got back home I was darker and more tan than I had ever been in my entire life," he said, and a friend commented on his darker complexion.

"Suddenly I felt really proud and beautiful," he continued, "and I realized I was wearing a shirt that said Boston across it, and I've come to realize that who I am isn't any one thing, but a composite of all my years of living."

Though she's still a teenager, Whigham said that growing up an in an interracial family has made her a confident person.

"I have learned to be confident about myself and just to be me and not try to be someone I wasn't," she said.

Maddie Whigam

Maddie Whigam

Helmer said that she struggled with being different as a kid, but now she's comfortable in her blackness.

"I definitely had some internalized self-hatred issues, but once I got to high school, I started to understand that blackness is not a monolithic thing," she said. "And I realized there was really no difference between me and another black person besides circumstance."

Do white parents need more resources about race when they adopt children of color?

Organizations like Pact and Amanda Baden's transracialadoption.net can help provide information and resources for parents, so that the adoptee children of color can be better served.

Helmer stressed the importance of making sure parents are well-informed about the racial obstacles their child could face.

"Oh my God," she said. "I see this especially with religious groups advocating for adopting people from different countries. They say, 'Oh I'm going to bring them to this super white area,' and sometimes there's no attempt to help the child feel like they belong." She said that white parents can't treat adopted children of color as if they're also white.

Helmer recommended that parents put themselves in "uncomfortable situations in minority communities," put their kids in after-school programs with minority kids or give them the opportunity to learn a home language if that's applicable.

"You can't treat the child the same as someone of your own race," she said. "They're missing out on a huge aspect of their own culture, and then they can have this weird internalized racism against themselves."

Riggs said that cultural training might be a good option, but it's not the most important thing.

"Maybe they're naive walking into the situation thinking everything is going to be perfect," she said. "Maybe there's some value in the opportunity to take a class, but at the end of the day, if that family wants to love the child then just let them."