'Made in America': How Sweatshops Exploit Immigrants to Make Your Cheap Clothes

By:

Jenny Dewey left Indonesia five years ago, lured to the United States by a human trafficker promising a good job as a nanny. She ended up in a Los Angeles, California, suburb, working for a rich white lady who “made me do everything — the cooking, the cleaning,” she told ATTN:.

She was exploited, undocumented, and unable to speak either English or Spanish, her waking hours spent inside someone else’s home 8,300 miles away from her own.

Finally, she said, “I ran away.”

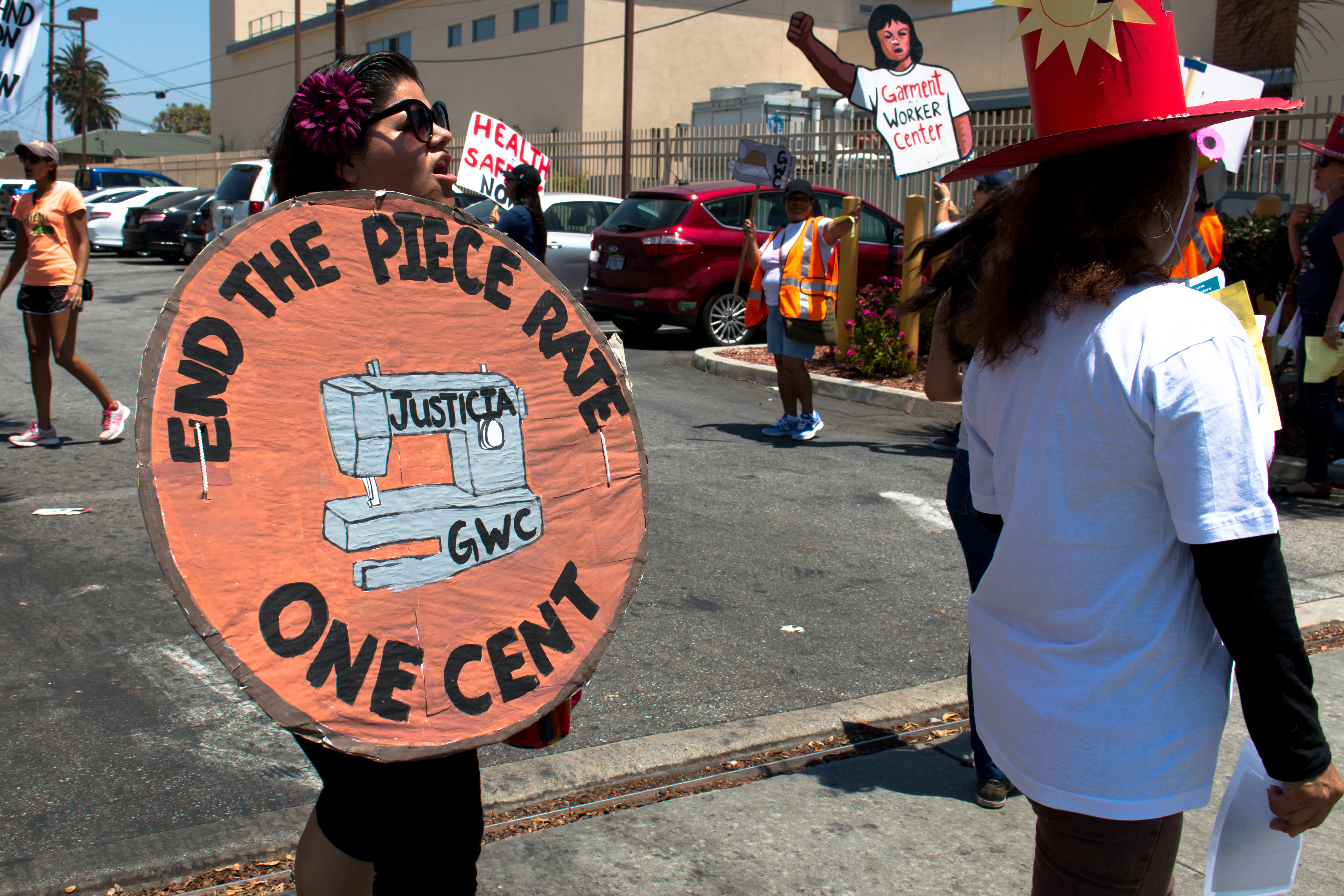

A woman protests outside a Ross in Los Angeles, July 22, 2017.

Like many undocumented migrants who come to the U.S. in search of better wages and a better life, she fled one exploitative situation only to find herself in another. She ended up sewing clothes, in a sweatshop that didn’t pay her. For three months she was robbed of her wages by an employer banking on the fact that she wouldn’t know how to fight back — or, because of her legal status, would be afraid to complain to the government, which in her eyes just might deport her.

“I was very scared,” Dewey said. “I didn’t know what to do.”

Her story is typical.

Of the 45,000 people who work in Los Angeles’ garment industry, the country’s largest, over 70 percent are immigrants, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 2016, the U.S. Department of Labor investigated 77 garment companies in the city and found that 85 percent of the time, they cheated their workers. Immigrants sewing clothes for brands such as Forever 21, Macy’s, and Nordstrom claimed earning as little as $4.50 per hour, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Dewey found another job that actually paid her, and with the help of the Garment Worker Center she was able to file a wage complaint and recover three months of stolen pay. She now sews yoga pants, and thinks her current employer is pretty decent. But she spoke to ATTN: at a protest because decent — a wage of $7 per hour in a state where the minimum is $10.50 — isn’t good enough.

“Los Angeles is supposed to be able to pay more money,” she said, “but we’re still fighting for minimum wage. It’s too hard.”

The protest, which took place on a warm Saturday in the immigrant-rich, Pico-Union neighborhood in Central LA, was outside of a Ross department store. The Department of Labor recently found that the popular discount chain was reliant on LA sweatshops paying sub-legal wages.

“Los Angeles is the wage theft capital of the country,” Anmie Shaw, outreach coordinator for the Garment Worker Center, told ATTN:. “We know that there are 13 factories that serve as sources of clothing for Ross. And the conditions in most of these places are really terrible.”

Pedro, an immigrant from Mexico who declined to give his last name, told ATTN: he spent three years working at a factory sewing clothes for Ross. “I worked for approximately 50, 55 hours a week and I made $300,” he said in Spanish, adding, “And they don’t have air conditioning.”

His advice to shoppers at Ross: “Don’t buy clothes here, because the workers in the factories? They’re not getting paid just wages.” (But it’s not just Ross: Pedro found another sewing job that treats him a little better, he said, but “it’s almost the same.”)

“The only place that has AC in the factory is the employer’s office,” Mariela Martinez, an organizer with the Garment Worker Center, told ATTN:. When her group interviewed more than 300 garment industry workers as part of a study with the University of Califronia, Los Angeles (UCLA) Labor Center, six out 10 workers complained of “excessive heat” and “poor ventilation” that “rendered it difficult to work, and even to breath.”

Mariela Martinez, an organizer with the Garment Worker Center, founded in 2001.

Amid a heat wave and a warming planet, that could kill, particularly since the garment industry’s largely immigrant workforce is paid by the piece, meaning there’s an incentive to work as fast as one can even when — as happened in July — temperatures outside the factory shatter 131 year old records. And if it’s 100 degrees outside? Inside, with sewing machines running 12 hours a day, it’s at least 2 degrees hotter.

Most retailers claim plausible deniability.

These garment factories are not owned by Ross or any other brand, but by subcontractors — that is, contractors for the contractors that these brands hire. And so long as these contractors claim to follow the law, and their subcontractors do the same, and so long as no one makes a real issue of it, there’s no real incentive for companies selling the final product to investigate the conditions in which they are made. And at the prices companies like Ross are willing to pay, Martinez argued it's near impossible for these subcontractors to fulfill an order while providing a living wage.

American Apparel was one exception, boasting that its executives worked in the same facility in Los Angeles as those making its clothes at a decent-for-the-industry wage of between $9 and $12 per hour. However, following a power struggle with its former CEO, the company declared bankruptcy and in January laid off its workforce, with just contractors left.

In a statement, Ross told ATTN: that the expanding and increasingly profitable company, with net earnings of $321 million in the first quarter of 2017, “takes labor compliance and violations very seriously. We require that all vendors, who are also responsible for their contractors or subcontractors, agree to uphold our ethical standards and abide by all applicable federal, state, local, and international laws.”

President Donald Trump’s crackdown on immigrants doesn’t help the cause of ensuring that these companies' pledges are fact-checked by their largely foreign-born workers, and his Department of Labor — facing the prospect of major budget cuts — isn't a reliable ally.

“Folks are afraid of speaking up,” Martinez said. “They’re told by employers they don’t have a right to minimum wage. And they’re told if they file a wage complaint, they’ll be deported. They get away with it by taking advantage of people’s need, and people’s fear.”

It’s Martinez who helped Dewey file her first wage complaint. Dewey said she found Martinez handing out flyers outside of the sweatshop that stole her wages. When ATTN: asked why she didn’t fight to get a legal wage at her current employer, too, she responded: “We are fighting right now.” The fight, in her eyes, is for hearts and minds of consumers, who need to demand the labor conditions the government won't enforce.

What LA’s immigrant workforce is fighting for is the country they were promised, and which many consumers in the U.S. believe is far better than the countries they left. Jonathan Cruz, 18, was passing out flyers to Ross customers. Originally from El Salvador, he told ATTN: that his mother used to work in a garment factory. The vast majority of clothing sold in the U.S. is made at sweatshops overseas, and conditions are generally better here in the U.S.

But the surprising thing, he said in Spanish, is “it’s not so different.”