Doctors Explain What It's Like to Treat Racist Patients

By:

At some point in their career, a minority doctor may have to contend with racist discrimination from patients. At least, that's the perspective of Dr. Alicia Fernandez, an attending physician at San Francisco General Hospital and a professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

"Patients simply say, 'I don't want you as my doctor, can I have another doctor?'" Fernandez told ATTN:.

Fernandez, who has more than 20 years experience practicing medicine, said that she had experienced this kind of discrimination personally. "The patient [said], 'I do not want a [Hispanic] doctor. I don't want you.'"

IMDB/Grey’s Anatomy - imdb.com

IMDB/Grey’s Anatomy - imdb.com

On Aug. 13, following the harrowing events in Charlottesville—which featured the biggest gathering of white supremacists in more than a decade—emergency room doctor Esther Choo fired off a series of 11 tweets about how white nationalism can even pervade health care institutions.

The first tweet in the series was retweeted more than 26,000 times.

Twitter users who identified themselves as medical professionals chimed in with their own stories of dealing with racist patients.

Others said they knew colleagues and loved ones who had similar encounters.

Sometimes patients request a different doctor in an effort to counter fears of discriminatory treatment.

In a 2012 research paper published in the UCLA Law Review entitled "Patients’ Racial Preferences and the Medical Culture of Accommodation," Kimami Paul-Emile, a professor at Fordham University School of Law noted, "One of medicine’s open secrets is that patients routinely refuse or demand medical treatment based on the assigned physician’s racial identity, and hospitals typically yield to patients’ racial preferences."

Her research illustrated that patients of all races make race-based choices about who treats them. The piece cited examples of black people being more likely to report being treated with disrespect by a physician of a different race, and that black, Latino and Asian patients reported problems communicating with physicians of other races at a higher rate than white patients. It also noted that patients feared that potential bias from doctors could influence decision making and recommendations for treatment.

Despite this, Fernandez stressed that bigotry is often at the root of such requests, especially when a white patient chooses to swap a minority doctor for a white one.

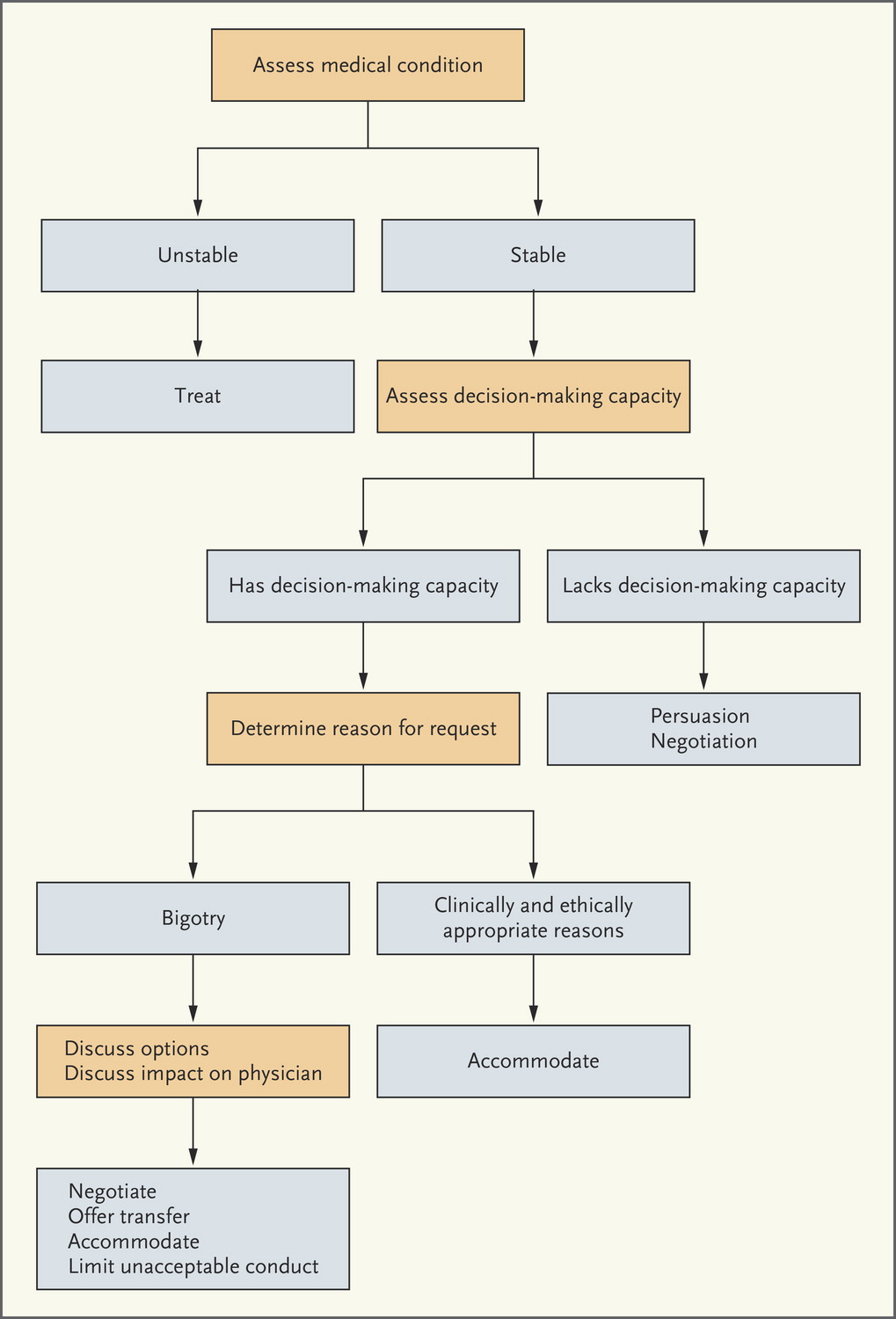

Fernandez published a guideline for doctors to follow when dealing with potentially racist patients.

In a 2016 piece in the New England Journal of Medicine entitled, "Dealing With Racist Parents," Fernandez, with Paul-Emile and two other co-authors, provided minority doctors and health providers an outline of what to do when patients refuse their care.

The New England Journal of Medicine - nejm.org

The New England Journal of Medicine - nejm.org

Fernandez said that in a clinic or outpatient setting, where the patients are usually in stable condition, the solution is relatively simple. "If they don't want to see me they don't have to see me."

But things get more complicated in an emergency room setting. There, a patient may be saying something racist because they believe it—or because they are ill and confused. Fernandez said in those cases, it's still reasonable for the attending doctor to find another doctor, if that's their prerogative and the resources exist.

But she stressed that it's not reasonable for the institution to offer another doctor to the patient, without the permission of the offended doctor.

"Minority physicians have the right to see patients, and its a violation of employment rules for employers to only provide white doctors." She added that "if the minority physician doesn't want to see the patient, it's not a problem," but that in cases where they are the only physician available or want to see the patient, "the institution needs to back up the minority physician, and simply say to the patient — this is what we have to offer, and let the patient seek care elsewhere."

.jpg?auto=format&crop=faces&fit=crop&q=60&w=736&ixlib=js-1.1.0) bidgee/Wikimedia - wikimedia.org

bidgee/Wikimedia - wikimedia.org

Sexism is also a factor.

Dr. Jaime McBride, an emergency medicine doctor and third year resident with Henry Ford Health System in Michigan, said that she has felt that patients have sometimes seemed uncomfortable with the idea of her treating them.

"I feel like we intuitively know when people are talking [as] if they're not comfortable with you," she said. "I don't know if it's a black thing, I don't know if it's a gender thing."

Fernandez said its not uncommon for minority doctors to have their expertise or credentials questioned, especially when they are young women.

"We hear that all the time, patients saying, 'are you really a doctor? Where are you from?'" she said. "It is reasonable to try, particularly if you're young looking, to reassure the patient you have the appropriate training. But some patients just can't believe that an African American woman might be a competent doctor."

Dr. Zainab Raji, an emergency medicine resident at Cook County Hospital in Chicago, said that she has dealt with sexism more than racism, and that, like other female colleagues, she sometimes gets referred to as a nurse, even after correcting patients numerous times.

"A Latina co-resident of mine told me just yesterday that she went in to see a patient who continuously referred to her as 'nurse.' Then, when she left the room, the elderly white patient told the white medical student that she [the patient] didn't believe [the co-resident] was actually a doctor."

Fernandez said it was important for co-workers in the healthcare industry to stick together when such incidents occur. And that talking about the discrimination that they experience can help illustrate just how pervasive racism is in our society.

“I think it's an important thing to bring to light, because when it does happen, it can cause a lot of pain to the individual doctor, and it can cause a lot of bad feelings for a healthcare team,” she said.

“Physicians have a lot of prestige and power, but even so, we are subject to this form of racist sentiment. By exposing that, we help people understand the way racism can sometimes work in our society.”