Our Prison System Is Even More Racist Than You Think

By:

We have an incarceration problem in the United States.

In a country of 320 million people, more than 2 million people are behind bars at any given time. More people are behind bars right now than live in the entire state of West Virginia, and our incarceration rate exceeds that of any other country in the world. Considering the high number of people that America locks up, the U.S. Department of Justice estimates are still stark—5.1 percent of the U.S. population will serve time at some point in their lifetime. That means that one person will end up in prison out of every 20 individuals.

Worse, those numbers skyrocket if you are a person of color. In fact, 1-in-3 black men will be incarcerated at some time in their lives, and the outlook improves only nominally if you are a Hispanic male (1-in-6 men).

The Sentencing Project - northstarnewstoday.com

The Sentencing Project - northstarnewstoday.com

Obviously, people of color—and black men in particular—are more likely than white individuals to end up behind bars. But that's only the start of the disparity. Black men are disadvantaged at every stage in the justice system, from arrest through parole, in shocking ways that run far deeper than simply who enters the correctional system. ATTN: has rounded up the top figures, which showcase the lesser known side of racial injustice in our justice system.

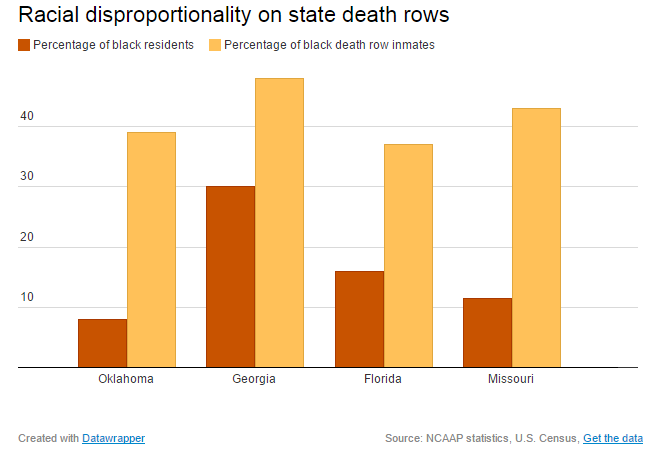

1. Race is likely to affect who receives the death penalty.

Black individuals comprise of almost half of the population on death row, but did you know that the odds of receiving a death sentence are nearly four times higher if the defendant is black?

In 2013, a survey examined aggravating factors that could predict the chances of a jury delivering a death sentence, including "murder with multiple stab wounds," "caused great harm, fear or pain," and "murder with another felony." Only two factors stood above the defendant's race as indicators that the jury would give the death penalty: "murder with torture" and "grave risk of death to others."

Conversely, statistics also show that we care less when a black person is a victim of a crime—delivering higher death sentencing rates for trials with white victims than when the victim is a person of color. In one large study examining trial verdicts between 1981 and 2002 in Ohio, offenders were twice as likely to be sentenced to death if they killed a white person than if they kill a black person.

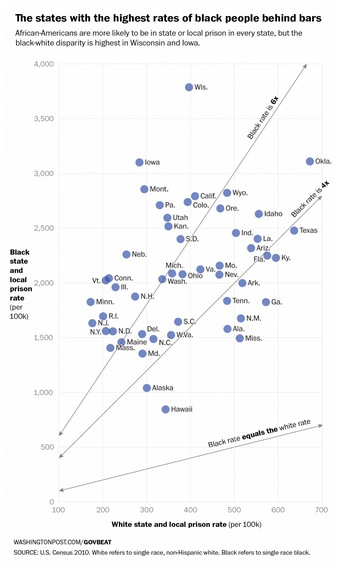

2. All states have disproportionately black prison populations, but states with the largest white majorities are also the worst.

Black individuals are more likely to be confined to state or local prison in all 50 states. But the states with the highest black-white disparities are also the most likely to have the least proportional prison populations.

In most locations, the black incarceration rate is at least four times greater than it is for white residents. For almost half of states, it's six times greater. Those numbers alone indicate painful fissures in our incarceration system. But for states such as Iowa and Minnesota, which have some of the lowest numbers of black residents per capita, the rate skyrockets. Black people are 10 times more likely in these majority white states to be jailed compared to their white neighbors.

The Washington Post - washingtonpost.com

The Washington Post - washingtonpost.com

States with larger black populations, particularly those in the South such as Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi, also expose this disparity. Where the black community is more proportional to the white community, black residents are only three times as likely as whites to be imprisoned.

The Atlantic - theatlantic.com

The Atlantic - theatlantic.com

3. Even before sentencing, people of color are at a disadvantage. They are are less likely to make bail than their white counterparts, spending more time in jail before they are even convicted of a crime.

The black community and the Hispanic community have much worse odds of making bail compared to white defendants, lingering longer in detention and suffering greater negative consequence over the long term. Hispanic individuals are less than half as likely to make bail compared to white people who have the same bail amounts and similar charges. Also, white suspects are 87 percent more likely than black individuals to be able to make bail.

This means that people of color comprise the bulk of those incarcerated before their trial, putting even innocent people of color in jail for longer periods than their white counterparts and placing them at additional risk for violence and mental health issues. In some cases, it can take years for a case to come to trial, causing immense disruption and strife to incarcerated people and their families.

More than half of inmates in the U.S. suffer mental health issues, either aggravated by jail or brought on by incarceration itself, and assault also occurs at higher rates in jail than in the outside world. Inside state prisons, suicide is a leading cause of death, with 40 suicides per 100,000 jailed inmates, according to the DOJ's statistics between the years 2000 to 2012.

4. Black offenders are more likely to receive harsher sentences for the same crimes as white convicts.

According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, black individuals convicted of a crime receive sentences that are 20 percent longer on average than white offenders jailed for the same crime. Sentences of black Americans also tend to be harsher. As of 2012, far greater than half (65.4 percent) of U.S. prisoners serving life without parole for non-violent crimes are black. (Black individuals are also 20 percent more likely to receive jail time in the first place.)

The picture becomes even more stark when we examine what happened when the U.S. Supreme Court stopped making federal sentencing guidelines mandatory. Prior to 2005's United States v. Booker, judges were required by the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 (SRA) to adhere to federal guidelines. These dictated a range for both the length and severity of an offender's sentence based on their crimes. During part of the time that SRA was enforced, the disparity between white and black sentence lengths fell to 5.5 percent. While still indicative of racial bias among judges, the gulf in sentencing length was nowhere near the 20 percent that it became after the United States v. Booker and the rise of advisory guideline.

5. Key decision makers in death penalty cases are almost exclusively white.

Of the U.S. counties in states that use the death penalty, the chief District Attorney is almost guaranteed to be white. One study found that 98 percent of top DAs in such counties were white men while only 1 percent were black. Research suggests that because white people assume different intent for black people accused of a crime regardless of age—even black children are seen as less innocent by white authorities—some groups believe this disparity contributes to the higher number of black men given a death sentence when compared to white perpetrators.

From one study on racism in America and it's impact on our view of criminality, even among youth: "Most children are allowed to be innocent until adulthood. Black children may be perceived as innocent only until deemed suspicious."

6. Once in jail, black inmates are more likely to be in solitary confinement, and are less likely to receive the same mental healthcare as whites.

The United Nations has stressed that solitary confinement is "always constitutes cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment" and has repeatedly suggested an absolute ban on solitary imprisonment for more than 15 days, referring to it as "torture" because of its negative impacts on mental and physical welfare. This disproportionately affects black inmates, who are 2.52 times more likely to be put in solitary than white detainees, as are Hispanics inmates, who enter solitary at a rate of 1.65 times the white prison population.

It isn't only that people of color end up in solitary in far greater numbers than white people in the U.S.; they are also vastly less likely to receive appropriate mental healthcare while in lockup, which leads to greater mental health issues on release—and can even keep them in solitary confinement for longer periods. According to a New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), black and Hispanic prisoners represented 40 and 46 percent of the prison population but only 16 and 13 percent of those admitted to mental health services. Meanwhile, almost a quarter of mental health patients were white, many of whom received care within the first seven days of their incarceration, while only making up less than 10 percent of those in prison.

The differences do not stop at who receives treatment. The biases run far deeper, into the diagnoses that inmates receive while under care. The same study also found that white inmates received more socially "legitimate" diagnoses—such as depression and bipolar disorder—which could keep them out of solitary confinement. Such diagnoses are seen as well-managed with medication, too.

What about black and Hispanic inmates? They more frequently were assigned mood, adjustment or antisocial personality disorders, which are seen as "pejorative" according to Dr. Daniel Selling, who was in charge of mental health at New York's Rikers Island jail until 2014. These diagnoses can also get an inmate placed in isolation or keep them there, rather than getting them out.

"Jail is a microcosm of society. A lot of society thinks that black and brown people are criminals," Selling told The Intercept. "You're using objective criteria, but three different people could come up with three different diagnoses."

7. Black people are also more likely to die while in custody, and are more likely to experience violence at the hands of prison staff.

Black inmates are less likely to have their sentences commuted, and are more likely to experience assault from correctional officers. They account for more than half of all executions that are carried out for death row prisoners (55 percent), despite that Black inmates are less than half of the death row population. In addition, there is a higher incidence of black prisoners becoming victimized by prison staff than white inmates.

8. Even for those who are released, people of color still get the raw end of the deal.

Black inmates receive longer probation periods when they are paroled compared to white prisoners. But how else are black parolees treated differently from whites?

A major key difference is income. While studies show no evidence of a difference in earnings prior to incarceration based on race, black ex-convicts show a steep drop off in their wages following their release from prison. Income growth on average fell by almost a quarter for black people leaving jail compared to their white peers. Because of inequalities in the diagnosis of mental health issues in prison, people of color are also subject to less financial assistance and other benefits associated with the mental health disorders that are most frequently given to incarcerated whites.

Slower wage growth and other post-incarceration challenges lead to higher recidivism rates for black ex-convicts, too, further perpetuating the cycle. Black former convicts were more likely to be re-arrested than whites (72.9 percent vs. 62.7 percent) and more likely to be sent back to jail (54.2 percent vs. 49.9 percent) according to the most recent U.S. DOJ study.

We are not doing enough to address the mass incarceration of people of color.

In the past year, our country has elevated the conversation about race and incarceration. From John Legend's comments at the Academy Awards to former Secretary of State and current presidential primary candidate Hillary Clinton's remarks that "too many black men are in jail," Americans are becoming increasingly more aware that there is a disparity. President Barack Obama's recent prison visit, the first for a sitting U.S. President, highlighted this, too, when he said:

"That’s what strikes me—there but for the grace of God [I could be in here, too]. And that is something that we all have to think about.”

According to Unlocking America, if black and Hispanic communities were incarcerated at an equal rate to whites, today's prison and jail populations would decline by about 50 percent. That's huge.

Beyond the racial tensions that these black-white disparities point to is a potentially greater truth. We still do not know how deep these problems extend because many states and some federal agencies do not collect racial data for prison populations. Further studies and surveys could show that more more inequalities might exist.