5 Charts That Prove the War on Drugs Is a Nightmare

By:

The War on Drugs has changed the criminal makeup of the federal prison system, a new report shows. More drug offenders are serving longer sentences in the U.S. than before the drug war took off in the 1980s, and it hasn’t really paid off.

Harsh sentencing laws enacted in the 1980s and 1990s have resulted in a dramatic rise in the number of federal inmates serving time for drug offenses, Pew Charitable Trusts reported. In the last 35 years, that number has increased from approximately 5,000 to 95,000 federal prisoners behind bars for drug-related offenses. It hasn’t come without a cost, either.

According to Pew, "these policies have contributed to ballooning costs" within the federal prison system, which now spends more than $6.7 billion a year. For every four dollars the U.S. Justice Department spends, one dollar goes toward these prisons.

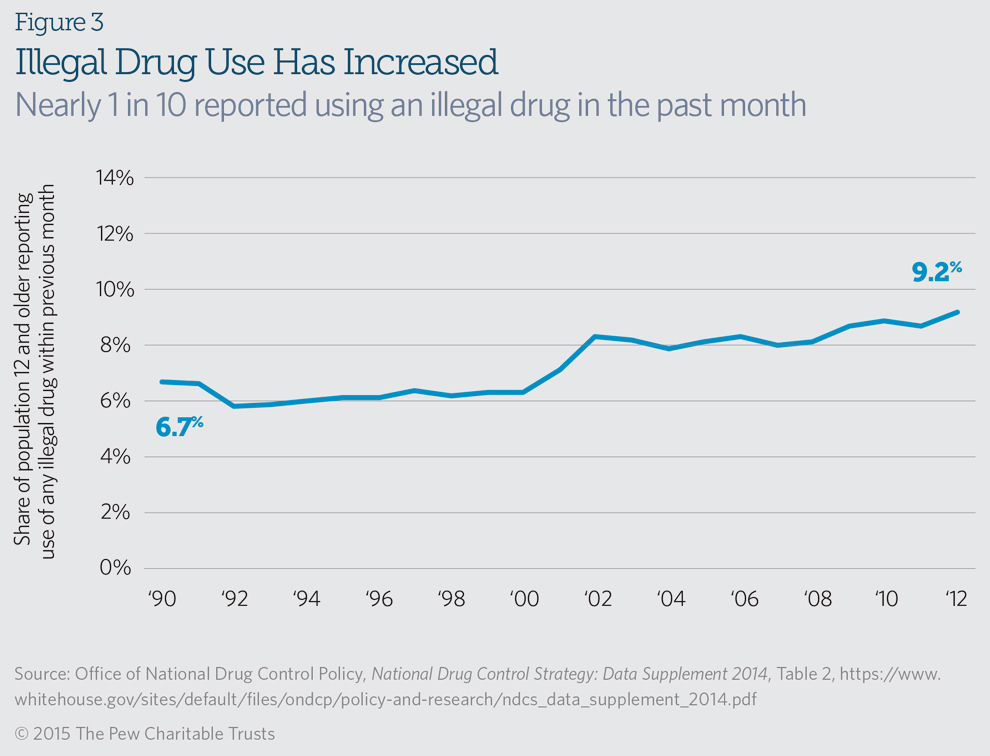

"Despite substantial expenditures on longer prison terms for drug offenders, taxpayers have not realized a strong public safety return," the researchers wrote. "The self-reported use of illegal drugs has increased over the long term as drug prices have fallen and purity has risen."

These four graphs, created by the Pew Charitable Trust’s Public Safety Performance Project, illustrate how the War on Drugs has played out and what, if any, effect it had on drug crimes in the U.S.

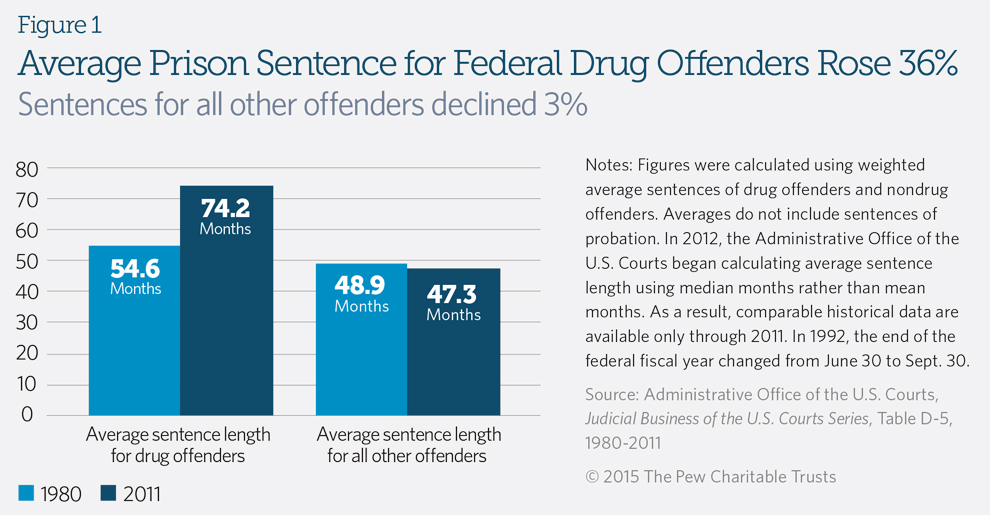

1. More federal prisoners are being given longer sentences than before the 1980s.

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

"Congress increased drug penalties in several ways," Pew wrote. "Lawmakers enacted dozens of mandatory minimum sentencing laws that required drug offenders to serve longer periods of confinement. They also established compulsory sentence enhancements for certain drug offenders, including a doubling of penalties for repeat offenders and mandatory life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for those convicted of a third serious offense."

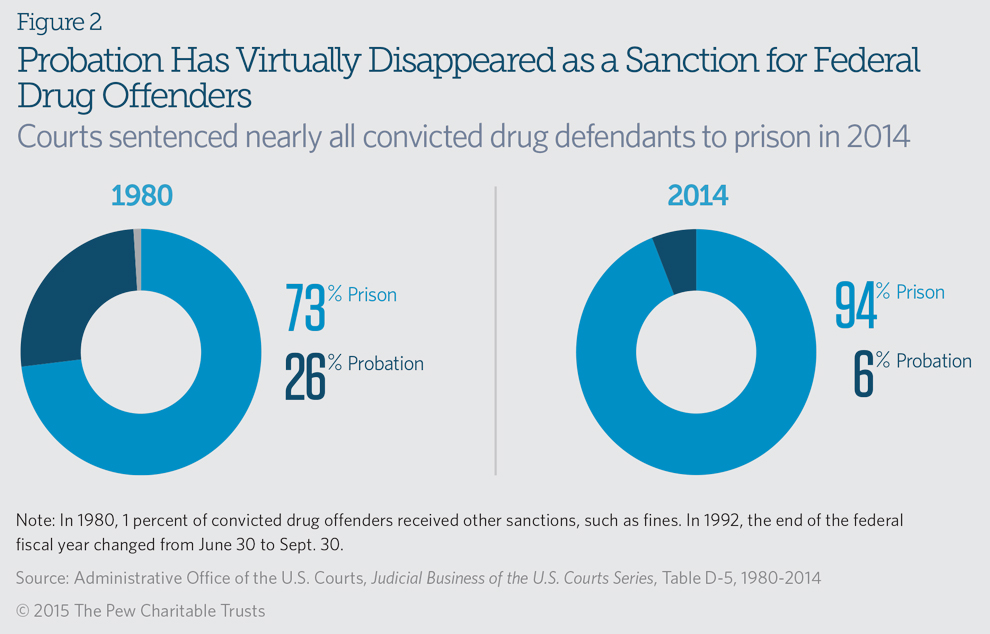

2. Sentences have become increasingly harsh for drug offenders.

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

Although federal law enforcement agencies such as the Drug Enforcement Administration have continued to devote resources to pursuing drug-related crimes, the long-term effect of those efforts has proven to be negligible—even as tougher sentences for drug offenders have gone into effect.

3. The War on Drugs hasn't stopped people from using illicit substances.

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

As Pew suggests, these laws have also been largely ineffective in terms of reducing drug crimes. If the goal of the War on Drugs was the reduce drug use, then the government might want to rethink its approach. The price of illicit substances, including heroin and cocaine, has dropped significantly in the last two decades, and rates of drug use in the U.S. have actually increased since 1990.

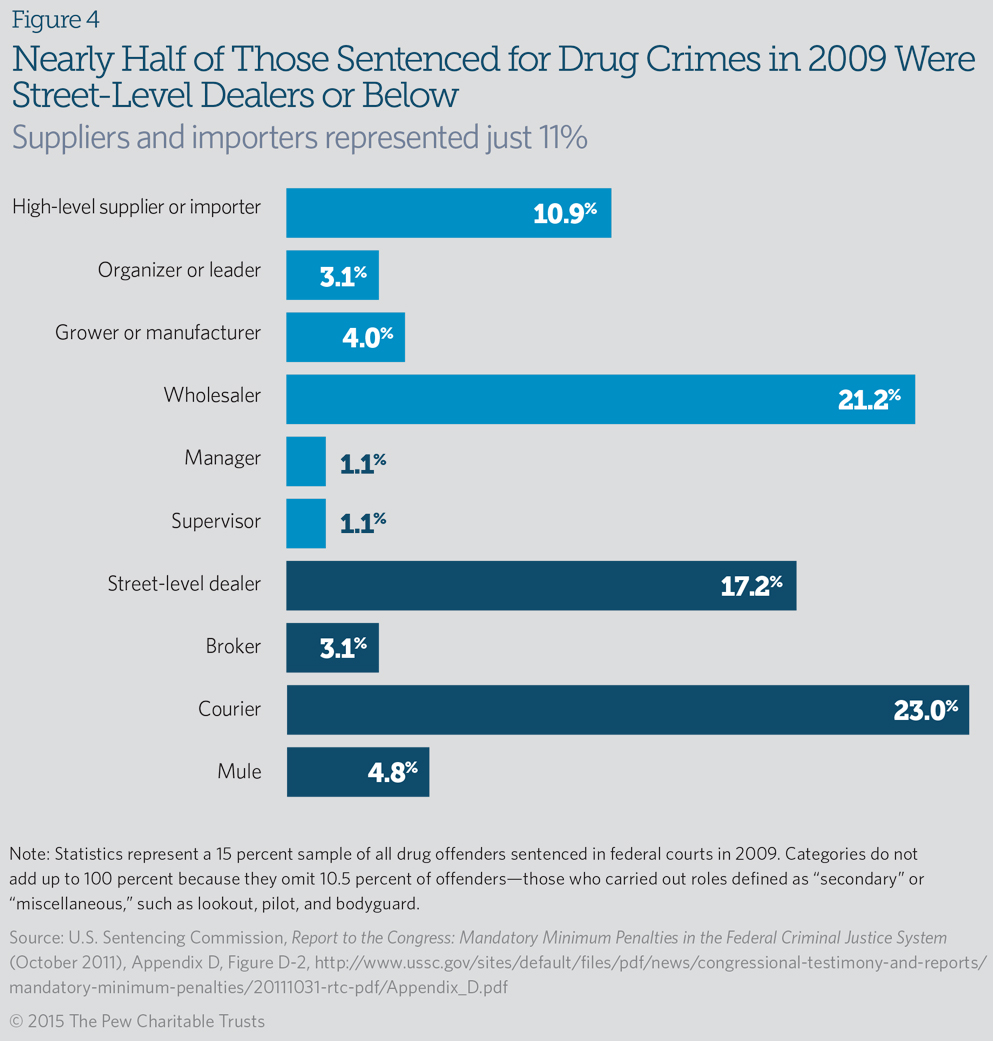

4. Federal law enforcement agencies have been targeting mostly low-level drug offenders.

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

Part of the reason for this problem is the way that law enforcement agencies conduct drug war-era operations—namely, targeting low and mid-level offenders while the commercial source of trafficking issues, commonly known as the kingpin, frequently gets off unscathed. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, high-level drug traffickers represent only 11 percent of the federal prison population.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 was designed to curb drug-related crimes by imposing a five-year mandatory minimum sentence for "serious" drug traffickers—those convicted of crimes involving a minimum amount of illicit substances such as 100 grams of heroin—as well as a 10-year mandatory minimum for "major" traffickers, defined as someone convicted of a crime that involves a lot more drugs, like 1 kilogram of heroin.

Yet nearly half of those sentenced for drug crimes in 2009 were street-level dealers or lower on the trafficking hierarchy, Pew wrote.

So the punishment does not tend to fit the crime. "The quantity of drugs involved in an offense is not as closely related to the offender’s function in the offense as perhaps Congress expected," a special report from the Sentencing Commission said in 2011.

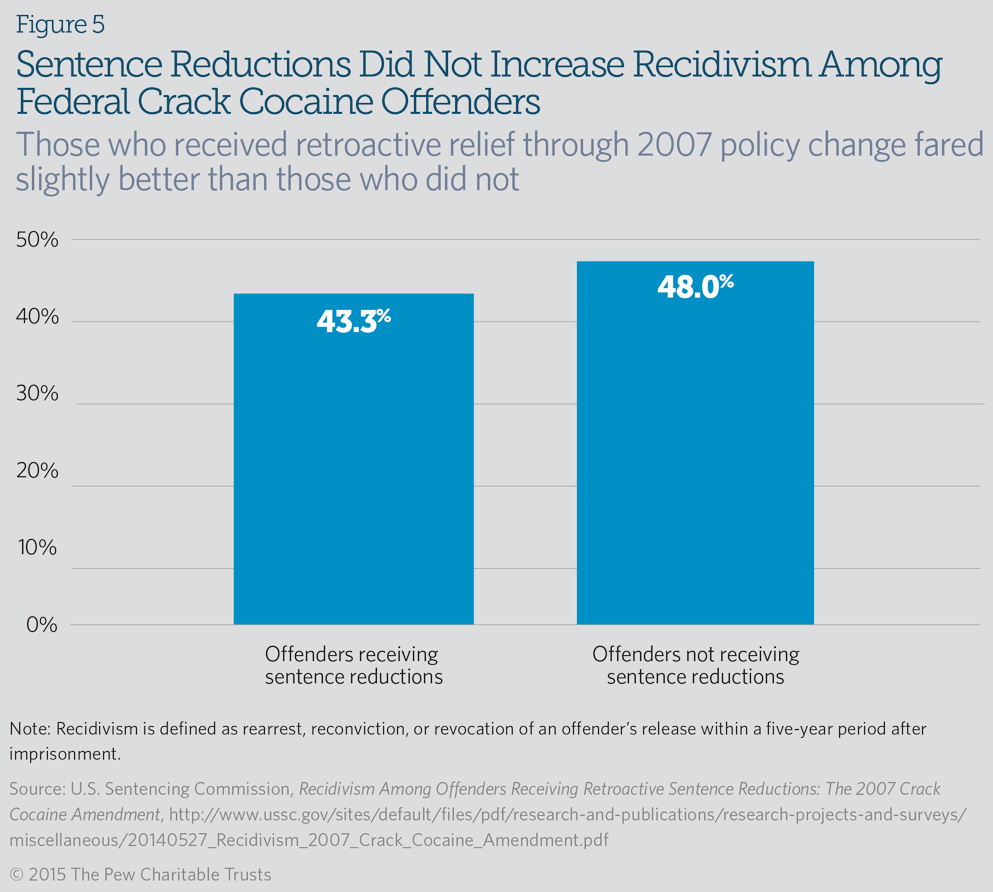

5. Reduced sentences does not translate into higher recidivism rates.

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

Pew Charitable Trusts - pewtrusts.org

"In response to rising public concern about high rates of drug-related crime in the 1980s and 1990s, Congress enacted sentencing laws that dramatically increased penalties for drug crimes, which in turn sharply expanded the number of such offenders in federal prison and drove costs upward," Pew concluded. "These laws—while playing a role in the nation’s long and ongoing crime decline since the mid-1990s—have not provided taxpayers with a strong public safety return on their investment."

"In response to these discouraging trends, federal policymakers recently have made administrative and statutory revisions that have reduced criminal penalties for thousands of drug offenders while maintaining public safety and controlling costs to taxpayers," researchers added.