The 3 Biggest Obstacles to Medical Marijuana Even Where It's Legal

By:

While a majority of U.S. states have laws on the books legalizing at least some form of medical marijuana, equal access to quality programs remains elusive.

California, for example, has one of the most established medical cannabis markets, reaching over 38 million people—or about 15 users for every 1,000 Californians. But the Golden State is a far cry from, say, Texas, whose lame-duck legal framework renders the program comparatively ineffective.

As a cohesive whole, the medical marijuana system in the U.S. has many limitations and is inconsistent, both in terms of separate state laws, but also in terms of nuances within a given state's legal program. For patients in need, that can mean substantial difficulties.

"There's variance state-by-state," Amanda Reiman, manager of marijuana law and policy at the Drug Policy Alliance tells ATTN:, "and then there are certain things that really will prevent access."

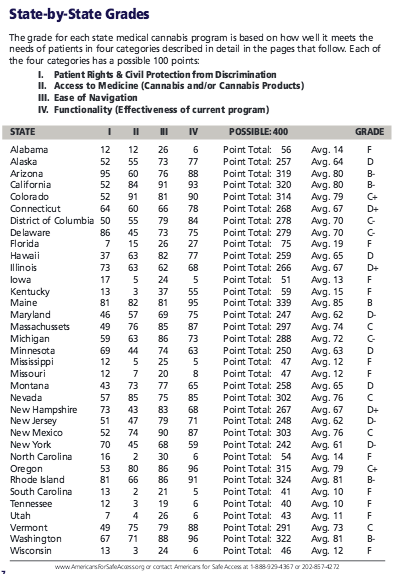

Across the board, states fall short in providing well-rounded programs that offer access to the actual drug as well as protections for those who use it. In fact, a 2014 report by Americans for Safe Access that graded state programs in terms of patient protections, access, physician availability, and overall effectiveness, gave no state anything over a B.

Americans for Safe Access - amazonaws.com

Americans for Safe Access - amazonaws.com

Here are the three major blocks to existing medical marijuana programs across the country.

Wollertz - bigstockphoto.com

Wollertz - bigstockphoto.com

1. The language of legalization laws.

There are several examples where lawmakers and healthcare professionals have been prevented from fully enacting medical marijuana laws due to the semantics of the legislation. It might seem like an insignificant hold up on a larger scale, but on a state-by-state level, the language of these laws can determine whether or not they are put into effect.

In Louisiana, for example, a medical marijuana bill that was first introduced in the early 1990s remained in the state senate, dead on its feet, until this year when lawmakers finally agreed to amend the language. It passed earlier this year. Originally, the law dictated that doctors would be allowed to “prescribe” medical cannabis rather than “recommend” or “certify”— the difference between implementation and impotence.

Under federal law, doctors cannot prescribe medical marijuana, even if a state legalizes the substance. They can, however, “recommend” cannabis—a loophole that enables healthcare providers to grant access to patients while avoiding penalization by federal law enforcement agencies.

A similar problem recently arose in Texas, where the semantics of a legalization bill has been blamed for delays and confusion concerning the execution of the law.

“On a certain level, the legislature should be commended for acknowledging the medical value of marijuana, and it is a historic vote in that sense,” Heather Fazio, the Texas political director for the Marijuana Policy Project told CBS. “Lawmakers missed several opportunities to amend the bill in ways that could have provided real relief to countless Texans. Not a single patient will be helped by this legislation.”

Big Stock / Iriana Shiyan - bigstockphoto.com

Big Stock / Iriana Shiyan - bigstockphoto.com

2. Access to willing and able doctors

According to Reiman, another "gate keeper" issue is a lack of doctors both willing and able to provide written recommendations for medical cannabis. In states such as Illinois and New York, the wording of the legislation doesn't preclude doctors from moving forward with recommending the drug to patients seeking it. But the stigma surrounding cannabis and the limited availability of educational programs for doctors to learn about it remain barriers.

"I think that [doctors have] a concern that they are going to get in trouble for recommending cannabis, and also I think that they feel they don't know enough," Reiman told ATTN:.

Although legislation was enacted two years ago, Illinois only has some 2,800 patients who have qualified for the program so far, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. Some peg low numbers and a slow start to stodgy medical associations and low participation in education programs; the Post-Dispatch reported that at least two major healthcare organizations in Southern Illinois prevent doctors from doling out formal recommendations since the drug is still illegal at the federal level. One possible reason is that the stakes are higher for doctors, who must submit a five-page form to the state proving a "bona fide physician-patient relationship."

Many doctors are wary of recommending a substance that they were not trained on in medical school. In New York, where physicians must obtain a license from the state through a two-to-four-hour health department course, many seem hesitant to do so thanks to the drug's stigma and to concern over testing federal laws. As the executive director of the Monroe County Medical Society told the Democrat and Chronicle, "[T]here's not going to be a lot of physicians who are going to rush to be the first ones to take the course."

According to Reiman, this should not be necessarily surprising.

"They don't teach doctors about cannabis in medical school, and they don't even teach them about the endocannabinoid system. So a lot of physicians, they feel [that] they don't know enough about cannabis to give a good recommendation that their patient try cannabis," she told ATTN:. Moreover, continuing education programs are still "not offered frequently enough for doctors to really to get up to speed in the way that they need to start giving a good number of recommendations," Reiman added.

Laurie Avocado - wikipedia.org

Laurie Avocado - wikipedia.org

3. Patient protection

In states like California, with established medical programs, patients face few legal protections in terms of employment and issues like child welfare and custody—where federal prohibitions can spell trouble for anyone made to take a drug test. The patient protection concerns for medical patients can largely be traced, once again, to marijuana being federally classified as a Schedule 1 substance. But Reiman says that's increasingly becoming a frivolous double standard.

"If I'm prescribed Xanax by my doctor and I get drug tested at work and I have Xanax in my system, that's fine as long as I'm not nodding off at my desk or doing something that's interfering with my work. If I'm a medical cannabis patient, that medical designation does not protect me in terms of employment," Reiman told ATTN:. "For all intents and purposes in California, having a medical card doesn't really afford you any kind of protection except for you being a personal consumer or cultivator."

Even in states where marijuana has been legalized for medical use, patients can still be prosecuted by federal law enforcement agencies such as the Drug Enforcement Administration. It is not often that the government gets involved in litigation against individual patients; they tend to target dispensaries. But when it does happen, it poses a significant challenge to legalization in the U.S.

The case of the Kettle Falls Five falls into this category. A family of five that lived in Seattle, Washington, the Harvey's each had medical marijuana recommendations and formed a collective garden that adhered to state law. In Washington, where cannabis was legalized in 2012, patients are allowed to grow up to 15 plants each, and between the five of them, they had approximately 70 plants growing at the collective.

When law enforcement agents came to the Harvey home in 2012, they weren’t initially concerned. At least one official was with the DEA, however, and another said that he smelled marijuana, the agents entered the home and confiscated some of the plants, leaving only 45. They thought that was the end of it until the DEA came back in full force eight days later, taking all of the family’s plants and edibles and even going so far as to seizing $500 in cash that one of the collective members had kept in a drawer in her bedroom.

They were charged with growing and manufacturing marijuana—which is, again, federally illegal under the Controlled Substance Act of 1970—and though they were acquitted of the most serious charges this year, the story of the Kettle Falls Five became a rallying call for legalization advocates who argue that the federal government should not be involved in pursuing cases against individual patients in states where marijuana is legal.

“The case against the ‘Kettle Falls Five’ became a rallying cry for legalization advocates, who said American voters have repeatedly approved medical marijuana laws to protect people in this situation,” USA Today reported. “The fact that federal prosecutors forged ahead even after Congress late last year ordered the Justice Department to leave alone states with medical marijuana just added fuel to the fire for legalization advocates.”

President Obama has since signed into law an amendment that was designed to limit the DEA’s ability to conduct raids against marijuana facilities in legal states. Though the federal law enforcement agency has seemed to resist this restriction, it has been seen a step in the right direction toward patient protection.

Kyle Jaeger contributed to the reporting of this piece.

This article was published in collaboration with the Drug Policy Alliance. To learn more about these issues, visit www.drugpolicy.org.