What Happened When a Reporter Worked Undercover at a Private Prison

By:

Private prisons are notoriously guarded about what happens inside their walls. But that hasn't weakened public interest into facilities that, collectively, hold more than 131,000 inmates across America, according to the U.S Department of Justice.

But this week, we got an unprecedented look inside.

Mother Jones reporter Shane Bauer landed a job as a corrections officer at the largest private operator, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), in order to get "an unconstrained look" inside the secretive industry. Because prisons rarely give unfettered access to journalists, private prisons even less so, Bauer spent four months inside the Winn Correctional Center in rural Louisiana gathering information.

What emerged is a chilling, eye-opening look at the inner-workings of a costly industry that has been criticized for putting profits before prisoners' well-being, routine mistreatment at the hands of guards, and generally abhorrent conditions — all on the taxpayer's dime.

Bauer's report highlights troubling training curricula from corrections officials. "If a inmate hit me, I'm go' hit his ass right back. I don't care if the camera's rolling," one instructor told new hires. He also experienced firsthand the way power can change a person's psychology: "I tell inmates to take off their hats as they enter. They listen to me, and a part of me likes that... for just a moment, I forget that I am a journalist."

Throughout the story, small fragments that speak volumes to the culture and tenor of CCA's prisons stand out.

Here's an exchange from Bauer's report between two officers talking about disciplining inmates:

"'Can't whup people's ass like we used to,' another officer named Gary says.

'Yeah you can! We did!' Chris says. He then sulks a little: 'You got to know how to do it, I guess.'

'You got to know where to do it also,' Miss Blanchard says, referring, I assume, to the areas of the prison the cameras don't see.

'We got one in the infirmary,' Chris says. 'Haha! Gary gassed him.'

'You always using the gas, man,' the third officer says."

Mother Jones - motherjones.com

Mother Jones - motherjones.com

Bauer also highlights lawsuits brought against CCA, some of which recount egregious and disturbing mistreatment of prisoners. In one case, which CCA settled for $250,000, a pregnant prisoner in Nashville was placed in solitary confinement so that guards could monitor her for proof of a pregnancy. After she was transferred to a hospital, prison guards watched as:

"[S]he gave birth and was immediately sedated. When she woke up, medical staff brought her the dead baby. She said she was not allowed to call her family and was given no information about the disposal of her son's body."

The report provides biting insight into why private prison companies might fight to keep their inner workings under lock and out of the public eye.

CCA, for one, has lobbied (successfully) against legislation that would open them up to the same public accountability laws to which government institutions are susceptible. Corporations explain secrecy efforts as protections against revealing trade secrets, which makes sense, given that they are for-profit entities in a competitive field.

Sentencing Project - sentencingproject.org

Sentencing Project - sentencingproject.org

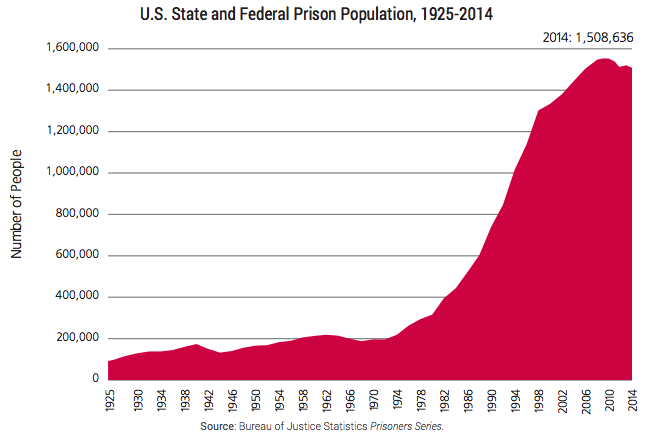

But that gets to a deeper, more existential question about the private prison industry in the U.S. as a whole. Corporations like CCA — or the other large corrections companies, GEO Group, and Management and Training Corp. — were born out of a need for more prison space in the 1980s, when incarceration rates soared (see the graph above). In recent years, however, mass incarceration has waned slightly, meaning that some facilities are feeling the squeeze of empty beds. And with a shrinking need for beds comes a shrinking need for private prisons.

Then again, that doesn't necessarily mean they're disappearing. In April, Colorado budget writers allocated $3 million of the state's budget to prevent the closure of a CCA-operated facility that was struggling with population declines, The Denver Post reported.

"They have a pattern of threatening to close prisons, to declare an emergency to get a bailout from taxpayers," Christine Donner, director of the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, told The Post. "This is chapter two of the same crap."

Read the full report at Mother Jones.